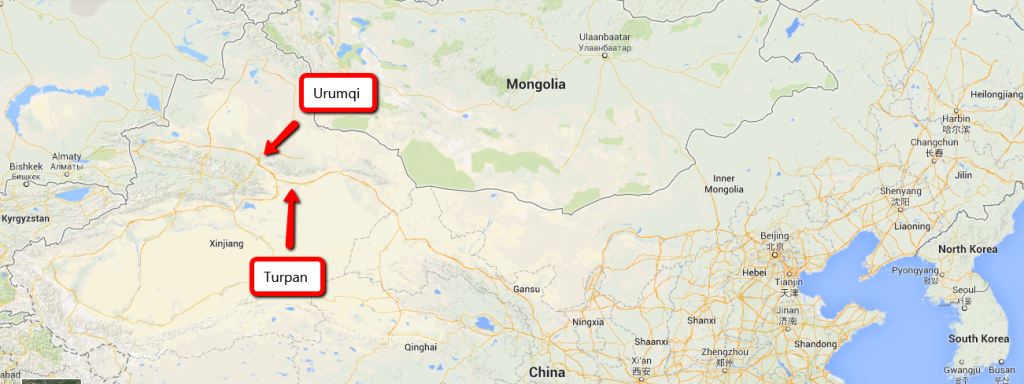

Turpan in Relation to Urumqi

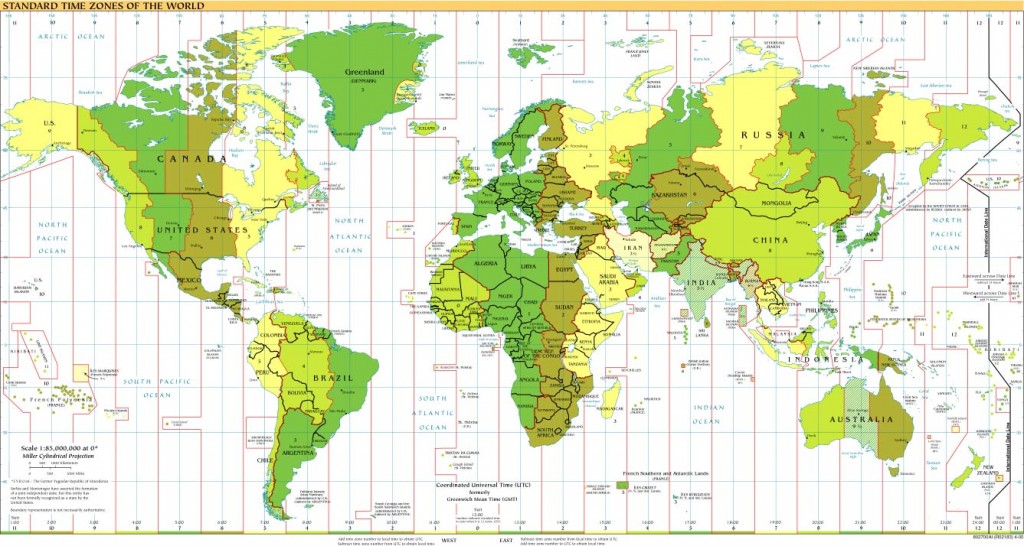

Xinjiang province is really two totally different places. The north and the south are distinct culturally, geographically and ethnically. The north is dominated by Han Chinese and our trips in the north were mostly snowy mountains and alpine pastures filled with Kazak herders.

The southern half of Xinjiang is desert or areas on the edge of deserts. The largest of these desrts is the Taklimakan Desert, about the size of Texas. Turpan, our first stop in southern Xinjiang, was only one hundred and twenty miles from Urumqi, just under a three hour drive, but the population was mostly Uighur, the Turkic Chinese who dominate southern Xinjiang.

Turpan had once been a thriving entrepot along the Silk Road. Moving out of China, the Silk Road split into two near Drink Horse One Army. Turpan was once the largest oasis-city along the Silk Road’s northern route and was once the seat of large empires that dominated sections of trade crossing from China into Central Asia, spreading Buddhism into China and silk into Rome.

- Uighurs in the Bazaar

Today, evidence of the Silk Road is easy to see. Skin tones amongst the city’s Uighurs vary from dark brown Central Asian features, with hints of Persian ancestry, to those with a pastier pallor, who could easily pass as Eastern Europeans.

- Selling Naan, a central Asian bread

Unlike Urumqi, which just feels like any other Chinese megalopolis, Turpan feels Central Asian. The town’s center has a large, raucous bazaar filled with a plethora of bread and carpet salesmen, crisscrossed by a labyrinth of narrow alleyways. Lambs hanging from tenterhooks and old men selling ice cream-here Turpan retains its Silk Road nature. Except for the Uighurs chatting into their iPhones, the bazaar feels like it would have looked about the same a thousand years before.

- In the hijab shop

Most of the people here in Turpan are Muslim, and many women wear some sort of head covering. Some wore the traditional Muslim scarf that wraps around the whole head, leaving only the woman’s face exposed. Others wore a Russian-style babushka, a scarf that wraps only their hair. I wondered, though I was not able to confirm, if this reflected some sort of cultural divide, the more conservative women wearing whole head coverings. Of course, some women wore nothing at all on their heads, preferring little black dresses and heels that screamed Moscow rather than Mecca.

- Babushka

In the bazaar, I saw several ice-cream refrigerators not used for selling ice cream. Instead, these fridges had been rigged up so that white hose emerged from the refrigerator’s interior and hooked back around, dangling in the air. From the hose’s loose end, a rusty liquid poured down into a red basin which had a mesh bottom and was mostly filled with dates, except for a small hole in the center, where the liquid drained back down into the fridge’s interior. The liquid they were selling was date juice, a traditional sweet Uighur treat.

- Fridge rigged to sell Date Juice

When I came up for a glass, the vendor filled up a cup straight from the hose flow, handing me the cup, icy and fresh.

I took a sip. I loved it, but it was the sugariest thing I had ever drank in my life. It tasted like I had been walloped in the mouth by some sort of sugar thug. After my first sip, I had to step back and take a deep breath. To wash the sweetness out of my mouth, I got a cup of ice cream.

- The date juice cycles from the freezer up through the hose and back down into the freezer through a bowl of dates

Turpan is the first time we have been able to jump into the deep end of the Uighur world, a living example of Silk Road heritage. Dunhuang’s amazing Buddhist caves were a stale, if incredibly beautiful, example of what the Silk Road had once been, but Dunhuang itself had died out and been forgotten a thousand years ago. Today’s town of Dunhuang had been built up over the last twenty years to serve tourists, like a beautiful piece of the Silk Road dead and preserved in amber.

- Leaving the Bazaar

But Turpan is alive and breathing. This is the real Silk Road.