Here’s the Video Galen put together of our time in Xian. Check it out:

Muslim Quarter

Xian is best-known as the fount of Chinese Civilization. It is the home of the Qin Dynasty, the dynasty that unified China in 221 B.C. It was here that the Qin Emperor was buried, along with thousands of his Terra-cotta Warriors. The Tang Dynasty was the height of Chinese Civilization and they made Xian into the center of the world, the Manhattan of the seventh century. People from all over the old world gathered within Xian’s walls to partake in the goods and glories of the world’s largest empire. For a thousand years, Xian was the center of Chinese Civilization.

However, Xian has another side; it is where China stops being so Chinese. In Xian, people’s faces begin to change. The change was most pronounced in the city’s large Muslim Quarter. Though the Quarter has been made tacky by so much pandering to tourists, it is largely populated by Muslim Chinese and, as we moved farther from the touristy area, seemed genuinely Muslim. Walking through the Quarter, we noticed a significant increase in facial hair. Most Chinese grow facial hair like twelve year old boys , but, here in Xian, there is a plethora of mustaches and a sprinkling of the long white beards of devout Muslim men.

Beyond the facial hair, the Muslims of Xian just look different. They have a stronger jawline and more pronounced cheekbones. Their eyes are less almond-shaped and their faces less round than most Chinese people. Unlike most Chinese, they have a much wider variety of skin tones, some a dark, sun-baked brown, some a pale white, all more like Turkish than Chinese.

The Muslims of Xian are classified ethnically as “Hui” by the Communist apparatchiks who decide these things. It is too simplistic to call them an ethnic group. Although many of them are descended from Muslim traders coming along the Silk Road from Central Asia, some of them are almost certainly descended from Chinese people who converted to Islam.

We wander outside the tourist section. Tucked in a corner is a small mosque. I wander in. Inside the mosque, there is nothing to suggest any Arab influence. The mosque looks almost exactly like a Chinese temple, though there is Arabic script hung from a few places. Clocks list the prayer times in the prayer hall, but the hall is flanked by two small, Chinese-style pavilions, each with a stone-carved stele, just like any other Chinese temple.

In an odd way, Xian is both the end and the beginning of Chinese Civilization. It was here that Chinese civilization began, and it was here that Chinese Civilization flourished, but it is also here that Chinese Civilization shows its first signs of giving way to the Central Asian Civilization that, along the Silk Road, made all the world their marketplace and occasionally, from atop the horse, made all the world their empire. The mosque embodies this fusion of the Chinese and Muslim worlds that is Xian.

Coins Only

Just a short vignette: after we got off the bullet train in Xian, we made our way to the subway. For some reason, the Chinese will often dedicate two or three of the five ticket machines as coin-only machines, despite the fact that the coins are rarely used in China and that each of the machines has a paper bill-feeder. At most stations, the regular machines have long lines while the coin-only machines lie unused.

Getting off the bullet train, I was the fifth person in line for the regular ticket machine. A fat man with a square haircut brushed past me, moving to the unused, coin-only machine. I watched him as he went through and selected the station name and the number of tickets he wanted.

Then, he pulled out a five RMB bill and tried to shove his bill into the bill feeder. The machine spit his bill back out at him. He fed it back into the machine after wiping it out flat. This process continued for almost a minute; each time the bill came back to him, he would either turn it a different way or try to smooth it out more.

I felt bad for the man, so I leaned from my spot in line and, in Chinese, told him, “You can’t use paper money here,” pointing to the sign on the machine that read in Chinese, “Coins only.”

He looked up at the sign, then at me, then back at the sign. “Oh,” he grunted, saying little more.

China has created so much wealth in such a short time. This man was a great example. He probably was born dirt-poor and now he is the richest businessman in his village and has money to throw around on big meals and a 520 RMB (approximately $85 USD) trip to Xian. But he was still just a bumpkin, totally unaware of how things work in the big city.

Bullet Train

City Lights, one of Charlie Chaplin’s most famous films, played on both the screens at the front of the car. Above it the speedometer flirted back and forth with three hundred kilometers per hour, about one hundred and eighty miles per hour. The numbers on the screen crept as high as three hundred and seven as we raced across the North China Plain.

Our project is about seeing China, talking to Chinese people and seeing China’s natural places as we travel west along the old route of the Silk Road, hitchhiking along the way. To get to Xian, the terminus of the Silk Road and the capital of many Chinese dynasties, we decided to take the newly built bullet train from Beijing, where Galen and I met up. In six hours, we covered almost seven hundred miles.

Like so many grand projects in China, the bullet train was impressive for its scale, its technological prowess and the rapidity it was produced with. The train’s speed blurred the landscape outside. Inside, the bathrooms were well-kept and the dining car was nicer than most restaurants in China. Beneath the train’s elevated platform, brown fields were dappled with peasants culling wheat from the arid ground. Shepherds herded sheep beneath us. It reminded me a little of northern India, thousands of villages squeezing everything they could get out of the arid dirt.

The cities where the train stopped seemed almost imaginary, emerging from out of nowhere. I would feel the tug as the train began to reduce its speed. The train’s speed would slip down to two hundred and fifty kilometers an hour, then one hundred and fifty, yet still, there was no sign of any urban development, only arid dirt and wheat farms, crisscrossed by tree-lined roads as far through the haze as you could see. Suddenly, a forest of cranes appeared on the right side of the train, each accompanying a thirty-story building.

A bullet train should only stop at major cities; if a bullet train were to stop at every rinky-dink town along its path, it would never be able to get up to its top speed, meaning its potential was wasted.

Yet, I had never heard of most of the cities we stopped at, though I had lived in China for two years. I had never seen these cities on any map of China. I had never met anyone from them. I had never heard of anything happening there throughout Chinese history. If I had not seen the miles of apartment towers stretching out towards the blue-gray horizon, I would not have believed the towns existed.

China has an amazing ability to build impressive infrastructure. That is a cornerstone of Chinese civilization, part of the myth of China. The Great Wall is the prime example. As we looked on at these cities, the sense of grandeur that I was first overcome with slowly gave way to skepticism. We looked at these cities, some of them seemingly completed, but we did not see many people in them. Their grand avenues were mostly empty. They had few shops or other commercial development, the hallmark of urbanism. One of the stops was even called New Rural Area City (新鄉市). Its name seemed to mock the idea that it could ever be a city.

Much has been reported in the Western media on cities that are built in China that have no one living in them, laying idle and unused, decaying after a few years. We only passed by them, so I don’t have much to say, other than to observe that they appear to be a facet of that ancient Chinese habit to impress through grand infrastructure projects without considering how the individual people who will use it fit into their scheme.

25 Years Ago, Nothing Happened Here. Move Along.

25 Years Ago, Nothing Happened Here. Move Along.

I arrived in Beijing late on the night of June 3rd. The city was somber. I was to meet up with Galen, the photographer, the next day. It was almost midnight when I made it into town. The first hotel I tried rejected me. They could not take foreigners, they said. They had hung a sign out advertising their hotel entirely in English. Move along.

The next hotel took me in. Laying my bags against the bed, I wandered around the city for a few more hours, getting my bearings. It had been almost five years since I had been in Beijing.

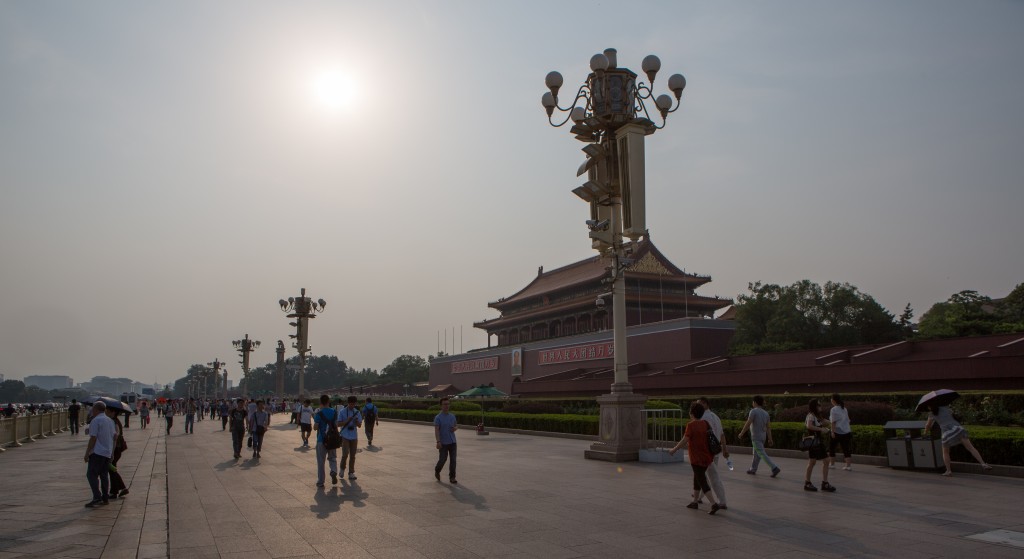

The next day, June 4th, I decided to go to Tiananmen Square. It is the tourist thing to do. Living in Beijing for half a year, I had rarely taken my passport anywhere with me, though it is technically required by law. Recognizing that June 4th was the most sensitive date on China’s unspoken calendar of sensitive dates, I decided to take it with me.

When I arrived at Tiananmen, they had set up white gates controlling access to the Square. “Passport.” A large man in a blue police uniform ordered. “Chinese visa.” He examined my papers and then waved me towards the security counter. He was checking my visa to make sure that I did not have a Journalist Visa. No journalists were allowed onto Tiananmen on June 4th. Why would journalists need to be in the Square that day? Nothing happened here. Move along.

25 years ago, the last remnants for a protest movement did not huddle on these stairs to exit the Square.

I wandered around the Square for half an hour, getting the requisite photos with Mao’s portrait. I am not a great smiler, but I tried to smile as ridiculously as possible. No reason not to smile. Nothing happened here.

An Irishman approached me, wearing a yellow shirt with “WTF?”printed on it. “Can you take a photo of me?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said. “By the way, I like your shirt.”

“You get it? I thought I’d give those bastards the finger.” The Irishman said, looking over the photo I had taken of him.

I smiled. “Nothing happened here. Move along.” He winked at me and disappeared into the masses of tourists weaving their way beneath Mao’s portrait.

On the square, police officers were approaching Westerners randomly, checking their papers. Somehow I escaped their eye exercise.

Walking around the Square, I realized that some of them were journalists. When I had entered the Square, I had watched the proper authorities scrutinizing a Frenchman’s papers, his Chinese partner looking on. They were both dressed as though they were trying to look like tourists. Twenty minutes later, when I left the Square, I heard the Frenchman and his Chinese partner asking Chinese tourists what they thought about what they were being told did not happen here twenty-five years before. The old Chinese couple they questioned was not interested. They waved their hands. “Nothing happened here,” they said, moving along.

Beijing Video

Rude Awakening

My entrance into China was a rude awakening. I was entering China from Taiwan via Hong Kong. Hong Kong being so small, I took the subway to the border and crossed there. I passed behind Hong Kong’s immigration and immediately a officer in a blue police uniform was yelling at someone. “Don’t cross that line,” he shouted at someone who crossed the line anyways.

Welcome to China.

The train station just past the border post was worse. The “line” was a seven hundred man push, with several people in blue uniforms leaning against metal posts in between intervals of opening gates and yelling at the flood of people pushing forward. I waited in a line for the ticket machine until I remembered someone had told me that foreigners were not allowed to use train ticket machines in China, though the machine had been equipped with English. I asked one of the guards where foreigners were allowed buy tickets. Leaning against her posts, she pointed towards another line and said nothing.

After pushing my way through the other line, the lady behind the window checked over my passport and I was able to buy a ticket. Behind the ticket hall, the waiting room was claustrophobic and had a menacing Soviet feel to it, dark and cavernous and packed with masses lugging plastic carpet bags with Mickey Mouse prints. Trains going to Guangzhou were delayed fifteen minutes. The masses groaned. There was almost no room to stand, much less to sit. The floors were covered with sunflower seeds, used cups of ramen and the remains.

I waited for about thirty minutes before a sign flashed at the front of the waiting area. “Don’t rush. Line up. Get on,” a man opened a gate and began yelling as we flooded past him to the two young girls checking tickets.

I had lived in China for two years, but I was last in China in 2010. For the past year, I have been living in Taiwan, studying Chinese literature. In Taiwan, they speak Chinese, but things are different. In the depths of the Shenzhen Railway Station, I had a realization; I understood everything that is said but nothing that is happening. I was disoriented like someone in their childhood home years later, after a stranger had been living there. Is this the China I left just four years ago. Has life in Taiwan warped my memories of what it was to be in China, or has China been warped?

Note: Most of our posts will have photos, but since I had not yet met up with our photographer, this post is lacking. Apologies.

Prelude

Before our journey really started, Galen and I meet up in Beijing. I had to meet with some people and it took Galen a handful of days to get over his Transpacific jetlag. While here, we walked around, taking in a few of the sites and practiced working together for photos and video. Here are some of the shots.

] Buddha in the Lama Temple[/caption]

What we want to do

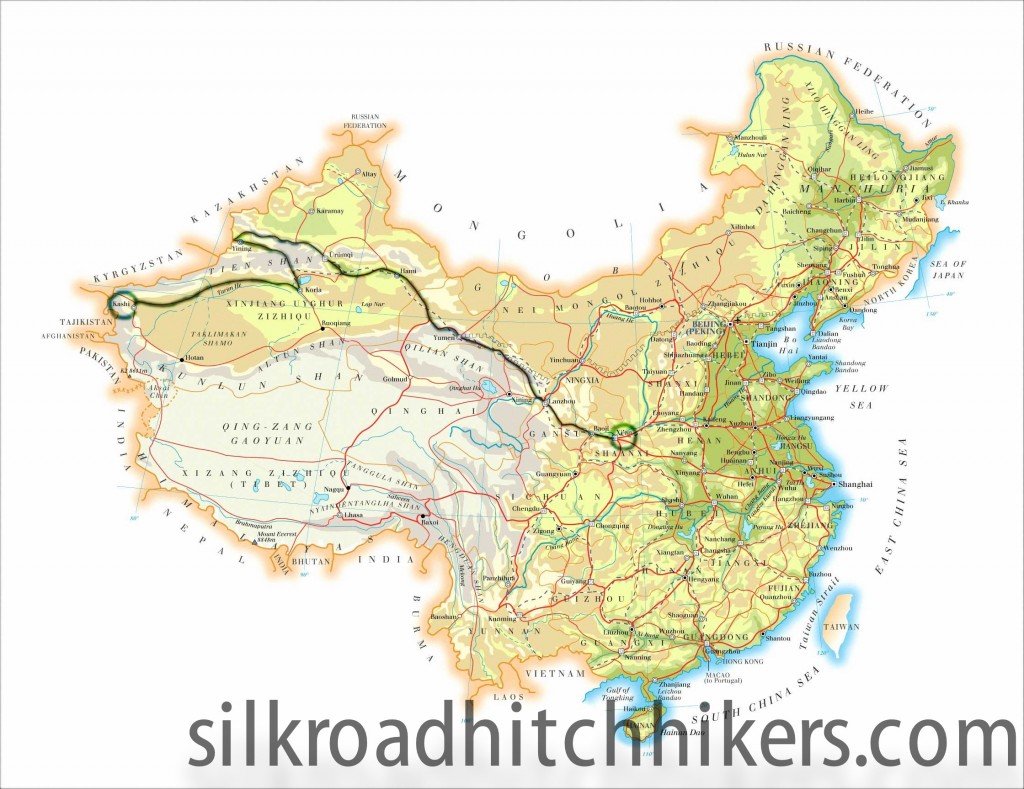

Since winning the 2013 Outside Magazine Adventure Grant, we’ve been waiting for our trip to start. We’ve packed our bags, booked our flights and gotten our visas from the Chinese embassy. Galen has his camera gear, and Lee has his iPad. On June 6th, we will begin the journey of a lifetime, hitchhiking the Chinese section of the ancient Silk Road and hiking in the National Parks along the way.

We will begin in Xian, the capital of dynastic China. Though it is more famous for its Terracotta Warriors, Xian was the eastern terminus of the Silk Road and its markets were once flooded with goods and people from all corners of the world. Today, the remnants of this Silk Road heritage can be seen in the city’s Muslim Quarter. The Quarter’s Grand Mosque, one of the largest in China, is a mixture of Middle Eastern and Chinese architectural elements and a metaphor for the mélange of cultures that the Silk Road engendered.

From Xian, we will hitchhike to Mount Hua, one of the most sacred mountains in China, around June 11th. For two thousand years, Mount Hua has been an imperial pilgrimage site and a Daoist retreat. With its importance in Chinese history, the summitting of Mount Hua in time to watch the sun rise from the East Peak has become one of the most important hikes in all of China, and we will be following in the footsteps of hundreds of Chinese hikers as we negotiate the foot-wide wooden panels nailed into cliff faces in the pre-dawn darkness.

From Mount Hua, we will hitchhike westward, moving out of central China. We will trace a route along the Gansu Corridor, the thin strip of land squeezed between the Gobi Desert and the plateaus of Tibet, where thousands of caravans have passed on their way into and out of China. Gansu is home to the Great Wall’s final tower, where Chinese empires dissipate into the deserts further west. In Gansu, we will be hiking in the Qilian Mountains, the northern border of the Tibetan world, and camping in the Badian Jaran Desert, home to some of the world’s tallest dunes. As we travel west through Gansu, the geography will be more desert-like and the people will be more Central-Asian-like.

In early July, we will cross into Xinjiang, China’s restive far west. This will be the most adventurous and challenging part of the trip. Unlike the rest of China, Xinjiang’s population is majority Muslim and the province has recently experienced ethnic strife. We will explore these issues in the context of Xinjiang’s natural world, camping out in Kyrgyz yurts in Sayram Lake National Park. We will also take part in the Mongolian Nadaam Festival, with competitions in archery, wrestling and, of course, horseback riding, to be held in central Xinjiang in late July.

Our trip will end in the borderlands between the Chinese and Muslim worlds. We will visit Tashkurgan, a Tajik city in China along the branch of the Silk Road over the Karakoram Range, just a hundred and fifty miles from K2. Here, we will hike in Karakul Lake Park and will try Buzkashi, a polo-like game played with the carcass of a headless goat. From Kashgar, north of Tashkurgan, we will pass out of China into Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to visit some of the most famous Silk Road entrepots like Samarkand and Bukhara.

Our objective for this trip is to not only see these fascinating sites and understand the history behind the world’s first globalization; we also seek to know how the Chinese see and use their outdoor spaces, so that, as the Chinese play a greater role in the world, their conception of what it means to hike, camp and climb can be better understood.

Lisa – Who are these guys?

Who the Heck are these guys?

Lisa Last

Although she won’t appear on the blog, and she’s not even in China, Lisa Last, Lee’s long-suffering wife is a vital, if untrumpeted member of the Silk Road Hitchhikers. Lisa is the one-woman support team, editing the blog, dealing with photo problems and handling other issues that have to be done in the United States, things that Galen and Lee can’t do from China.

But Lisa played a much deeper role in the project. In fact, the Silk Road Hitchhiker Project would never have happened without her. It was Lisa who actually saw the announcement on Outside Magazine’s Facebook page that eventually led Galen and Lee to apply for and win the $10,000 Outside Magazine Adventure Grant. Although Lee is a long time reader of Outside Magazine, the grant was not announced in the print edition of the magazine, but only on their Facebook feed. Lee and Galen had long been kicking around the idea of hitchhiking the Silk Road, but if Lisa had not seen Outside Magazine’s announcement on that afternoon in May, the project would have probably still just been a dream.