Kashgar

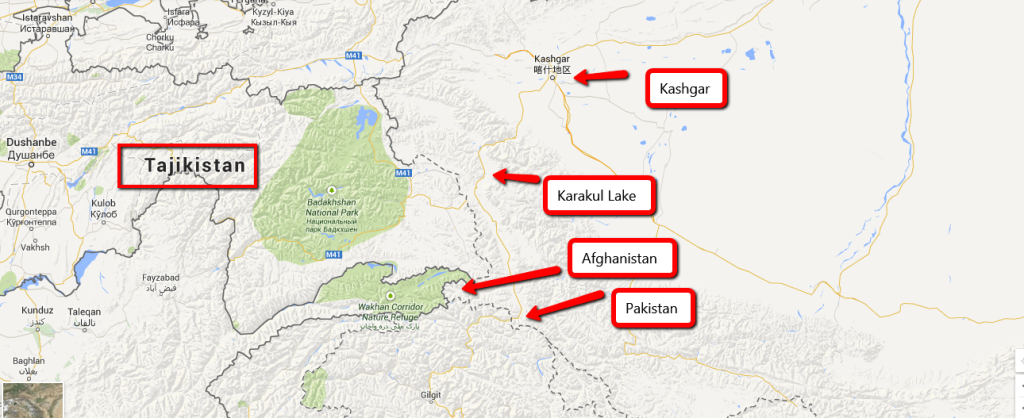

We were trying to leave Kashgar for a lake on the Karakorum Highway, the world’s highest international highway, where we would camp out at Karakul Lake, just sixty miles from the town of Tashkurgan. Not sure where we could hitchhike from, we had originally wanted to take a bus there and hitchhike back. I went to the bus station a little before eight in the morning, Xinjiang time, to get two tickets to Karakul Lake or Tashkurgan.

When I asked at what time the bus to Tashkurgan was, the woman at the bus stations ticket window replied to me with a simple, English, “No.”

“What do you mean, ‘No’?” I asked in Chinese.

“No.” She responded. Apparently, she only knew a single English word, and she thought the best strategy for explaining the problem to a foreigner was to stick with this one word.

“I don’t understand you. Speak Chinese, please,” I said, getting pushy with her.

After several seconds of consideration, she explained to me in decent but halting Mandarin that “All tickets today sold.”

I began to panic. “Sold? But tickets can only be bought the day of. How could they only be sold, it’s only eight in the morning?”

She shrugged. “Tomorrow, come earlier.”

“Tomorrow? Is there no other bus station with tickets going to Tashkurgan today?” I asked

The woman at the ticket counter gave me a variety of answers, some contradicting others. Based off of what she told me, I guessed that there might be another place where we could get to Tashkurgan, though it probably would not be a bus.

Outside the station, a line of men were selling rides in vans to a variety of towns. I approached him. “Are there any vans going to Tashkurgan?”

He shook his head, “No,” but told me the name of a location where I could find vans to Tashkurgan. But I had no idea where this location was. I asked him to write down the name of the place. Instead, he took me to a cab waiting outside the station and told the driver where I wanted to go.

Unfortunately, the cab driver was Uighur, and he only barely spoke Mandarin. He nodded when the man told him where to go, but, after turning on his engine, he looked back at me and asked, in his only basic Mandarin, “Where you go?”

I rolled my eyes and waved the man who knew the place back over. Again, the man explained the name of the place to my driver and where it was. My driver nodded again and took off. Still not sure if he really knew where to go or if he was again bsing, I asked the cabbie if this place was far from here. Not answering me, he laughed.

We drove past Kashgar’s old town, farther outside the city center than I had ever been, yet still, the cab ride was only $1.10USD. I was dropped off at a parking lot in a suburban area of Kashgar. Behind the parking lot were some new apartments and a long line of restaurants and convenience stores. Nearby was an office which handled many of the affairs of Tashkurgan County. The place was so remote that many of the bureaucrats who managed the county worked and lived down here in Kashgar, only going up to Tashkurgan when business required.

The place is so remote that few major suppliers serviced Tashkurgan. The roads, the elevations and the distances made it too difficult for most semi-trucks to make it up to the town. The only people willing to supply Tashkurgan were a fleet of private pickup trucks driven by Chinese rednecks, loading up their beds down with supplies and filling up their cabs up with four passengers. They gathered outside this Tashkurgan Affairs Office, waiting goods and people to haul up to Tashkurgan.

At first, I talked to a man with a van taking a group of people up. He had only one space, for 100 r.m.b. and he wanted to leave soon. That was no use to me as I had neither my bags nor my Galen, and the two of us would not both fit. I left the van, returning to the hotel. We packed up, storing much of our gear in the hotel, and checked out.

When I returned to the Tashkurgan Affairs Office, the van had disappeared. The only person willing to take us up was a pickup truck driver, a Uighur, and he would only do it for two hundred r.m.b. per person, $60USD for the two of us. I was not willing to pay that much, and the Uighur was not willing to negotiate. One thing this trip has taught me is that Han Chinese are great in business in part because they are always willing to negotiate, even when Uighurs or Tibetans or Kazakhs are not; it is one of the many things I admire about the Chinese.

Other pickup drivers were milling around, so I asked each of them but they all told me they were not willing to take us, because we were foreigners. They could not or did not explain why, other than to say that things would be more difficult for them if we were not Chinese passport holders.

Finally, I found a driver hanging out in a restaurant. His truck was loaded with a sign for a China Meteorological station, and his cab had several people milling about inside.

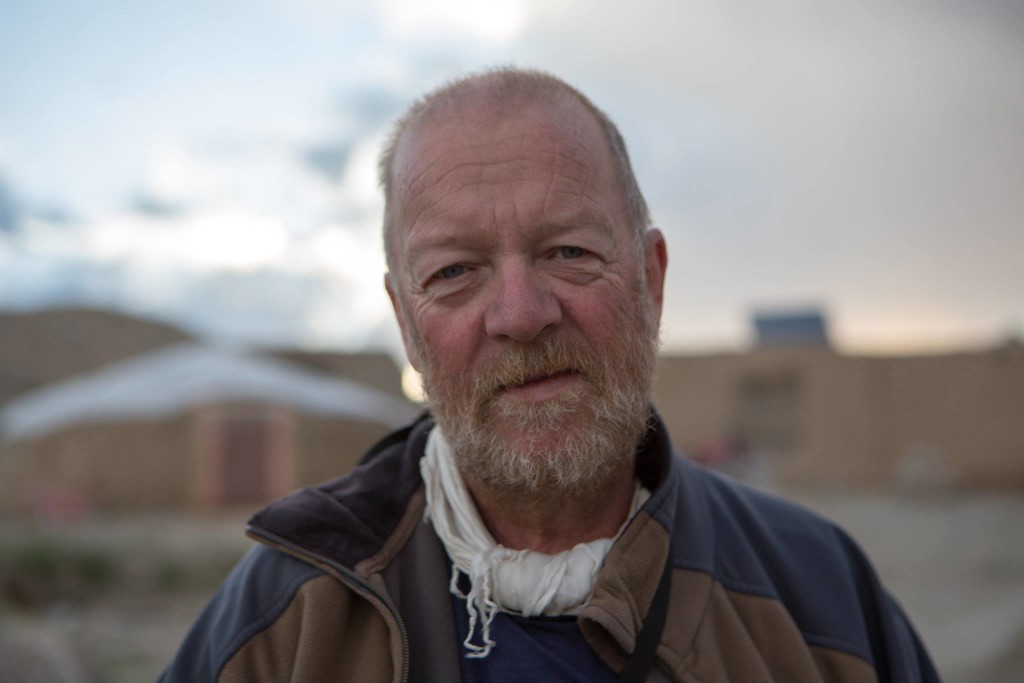

Our Pickup

“You a pickup driver?” I asked.

“Yeah?” He looked at me.

“Do you have space for me and my friend?” I asked.

“No foreigners.” He said, digging back into his noodles. “There is a checkpoint outside of Tashkurgan. It is too much trouble to get foreigners through that checkpoint.”

“We just want to go to Karakul Lake, not Tashkurgan.” I told him.

He contemplated my proposal. “Sure. 150 r.m.b. per person.” Galen and I agreed, throwing our stuff into the bed of his pickup, along with other random junk he was transporting including a four-foot tall sign for the China Meterological Administration.

When we pulled out of the parking lot, the Uighur who would not negotiate the seat price was still standing around, his passengers growing increasingly impatient.

The Truck that took us up to Karakul Lake