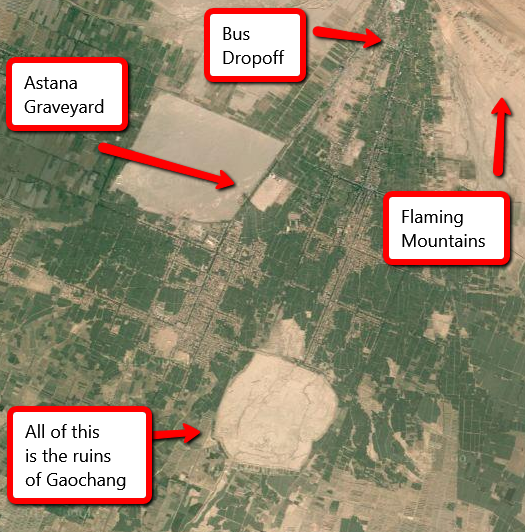

Galen was down sick again, so I took the camera out by myself to see the ruins of Gaochang. The bus dropped me off where I had expected, at an intersection in Second Fort Village. I began walking in the direction of the ruins of Gaochang.

Interested in all aspects of village life, I tend to be snap-happy in these situations. The width of an alleyway between houses, water running through roadside canals, children screaming as they play, each of these things teaches me something about Xinjiang, and I naturally want to take pictures of them.

And that is exactly what I did.

Galen has often talked to me about how the camera is his language; though he does not speak Chinese, he can form a bond with people by taking their photo and then showing them the picture. Instantly, most people become his friend.

Not sure about this stranger

That day, I felt the power of its language. I took photos of the girls playing from a distance. At first, they seemed a little standoffish at a stranger, a foreigner to boot, taking pictures of them. Then, I turned the screen to them, showing them the photos I had taken. When they saw their faces on the screen, they erupted into a storm of giggles. Soon, they were posing for me, wanting me to take more. I obliged. When I walked away, continuing towards the ruins, the gaggle chased after me, waving and screaming, “Bye, bye.”

I continued down the road, taking pictures of whatever I wanted. Hanging outside a school, I saw an interesting poster, and I was about to take a picture of it. But out of the corner of my eye, I could see two men in blue uniforms walking my way. I tried to act normal, hoping not to draw their attention. Further down the road, I could see a sign for a police station. They were probably just taking a stroll from the station, I thought.

They were walking closer and closer to me. I did not look at them.

I had not even noticed the woman in a white dress walking beside them, but it was she who spoke to me. “Excuse me,” she said in her best broken English, the two uniformed cops stopping beside her. “Why are you taking photos?”

I looked at her, surprised. “Because I am a tourist.”

“What are you here to see?” she began the interrogation, translating each of my answers into Uighur for the two uniformed cops.

“I am here to see Gaochang,” I said.

“Gaochang is very far.” She responded.

“No, it isn’t. It’s just down the road here.” I shot back at her.

“You come by taxi?” she asked.

“No, I came by bus.”

“Bus?” She puzzled over the matter for several seconds, but appeared to not be able to come up with the English she wanted to continue this line of interrogation. She had trouble believing that some foreigner who could not speak Chinese could really travel all the way here by bus.

“What is your work?” she asked.

“I am a student.” I told her.

“You have a student card?”

I nodded.

“Show me.”

I fumbled for my wallet, handing her my old University of Georgia card instead of the student card that I had from my year studying Chinese literature in Taiwan. I wanted to give no hint that I spoke Chinese. As long as we were speaking English, I had some control over my interrogation.

The woman looked over my card. Saying something in Uighur, she handed the card to the two cops. They examined it, photographing it with their phone.

“Do you have passport?” she asked.

“No. It is in my hotel.”

“Which hotel?” she asked.

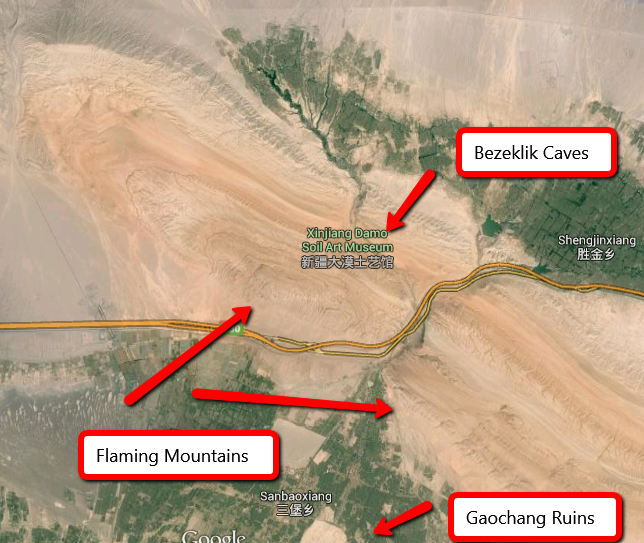

“Flaming Mountains Hotel. In Turpan.” I said. Immediately, she translated the hotel’s name into Chinese. This was the only part of their conversation that I could understand, since it was the only word they said in Mandarin.

“This place is not city,” she told me. “This is not Turpan. This is a rural area…and in rural area, many people do not like their photos taken. They are conservative. Please put your camera away, and not take it out until you arrive at Gaochang.”

I agreed to do this. They handed my student ID back to me, and I walked away quickly. For the next ten minutes, I swore a man on a black motorbike was tailing me. I walked further, getting into an even more rural area, and the man disappeared. I am still unsure whether the black motorbike had really been following me, but the encounter had left me paranoid.

Later, after visiting Gaochang, I returned to Turpan. A police car was parked outside where we were staying, the Flaming Mountain Hotel. The cops were exiting as I entered. They did not seem to notice my presence. When I asked the receptionist whether the cops had anything to do with us, she told me, “Don’t worry about it. They were just investigating us a little. No big deal.”

For several hours, I turned these events over in my head. At first, I seriously considered the possibility that someone had been offended at me taking photos of the little girls at the beginning of the trip. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that was unlikely. We had been in rural areas before. No one seemed bothered by us taking pictures.

The explanation for my interrogation was more insidious. Perhaps, they had been alerted to my presence by someone calling about a foreigner taking pictures, but that was not the reason they had gone to the trouble to find an English speaker, interrogate me and send someone to investigate my hotel.

With the outbreak of ethnic violence, anywhere Uighurs lived had become sensitive. The authorities were on the look out for anyone who was not a tourist, anyone who might be a journalist.