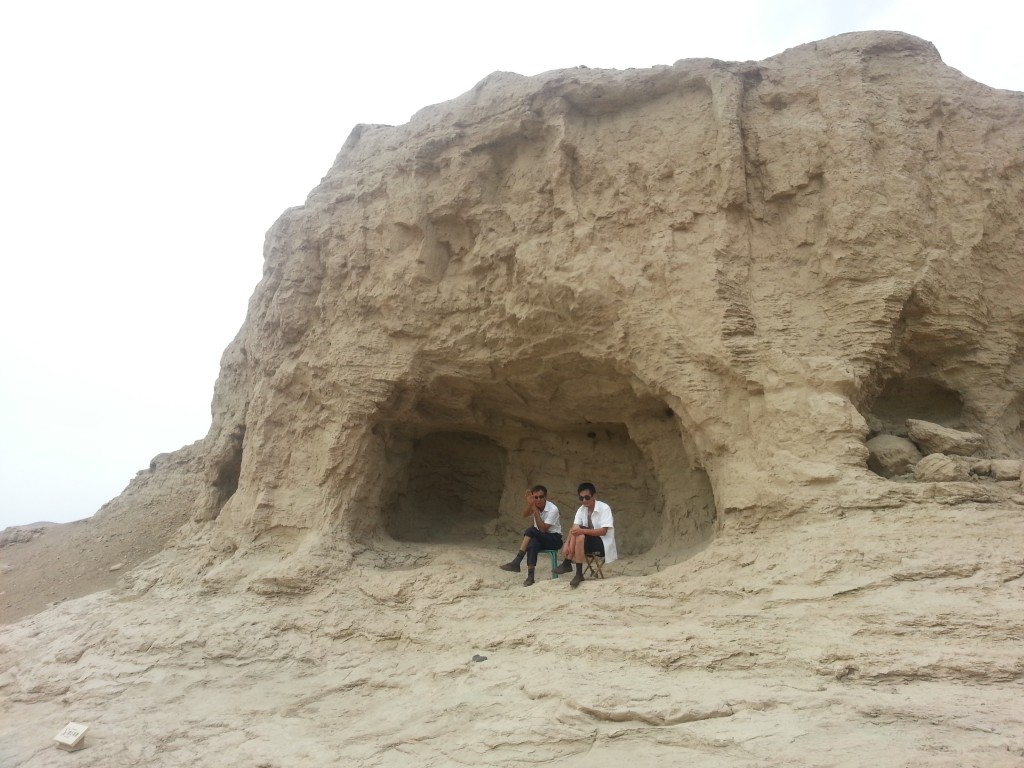

The sun was beating down on us. We walked the half mile down the road to where the Bezeklik Caves compound was.

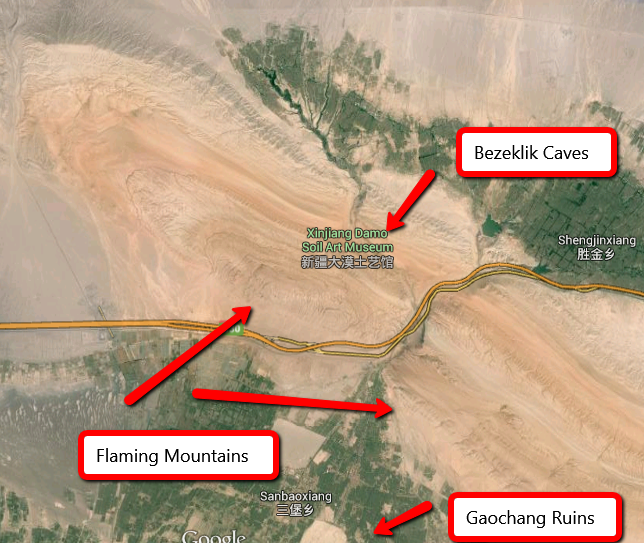

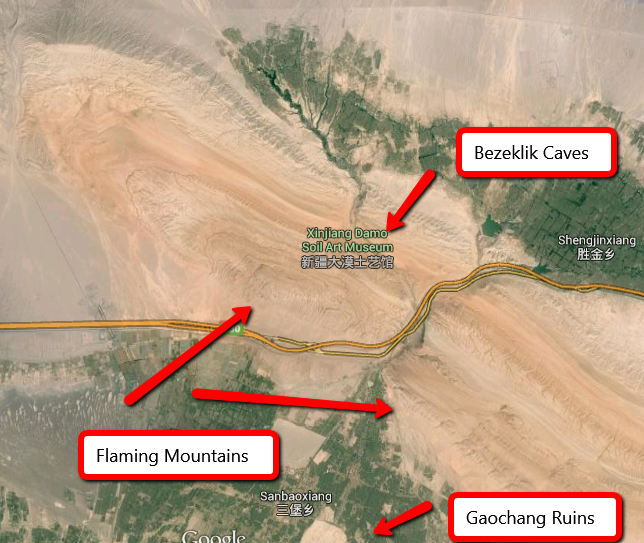

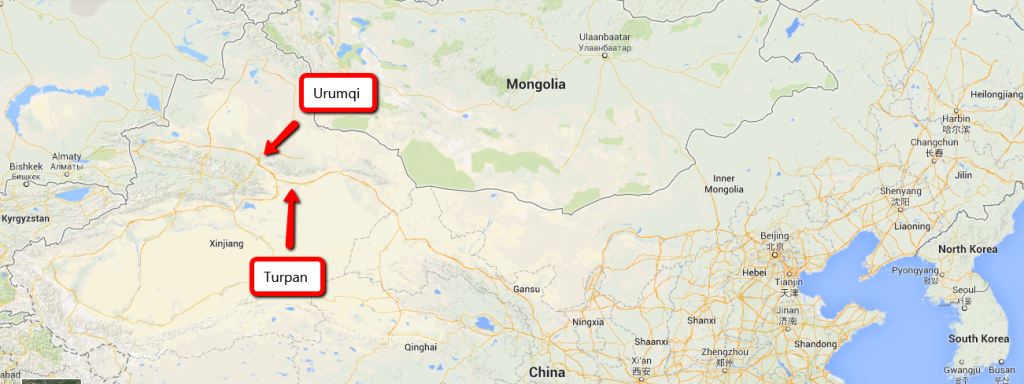

Caves is not an accurate way of describing Bezeklik. Bezeklik is actually a series of man-made grottos carved into the side of a tall cliffface above a small river. The Mutou river runs from Shengjin in the north, a green split of dense vineyards on the north side of the Flaming Mountains. From Shengjin, the river carves a canyon through those mountains, before pouring out into the Turpan Basin, the lowest elevation in China.

In Chinese, Bezeklik is called the Thousand Buddha Caves. There are only seventy-seven caves remaining, and many of these have been badly damaged. In the past hundred and fifty years, explorers from the West and Japan snatched some of the paintings up, chiseling the artwork straight off the grotto walls. Others were destroyed by Uighurs after they converted to Islam or Maoists when they were in an anti-religious fervor.

You are no longer able to view this piece of art in China, though it may be on display at Harvard

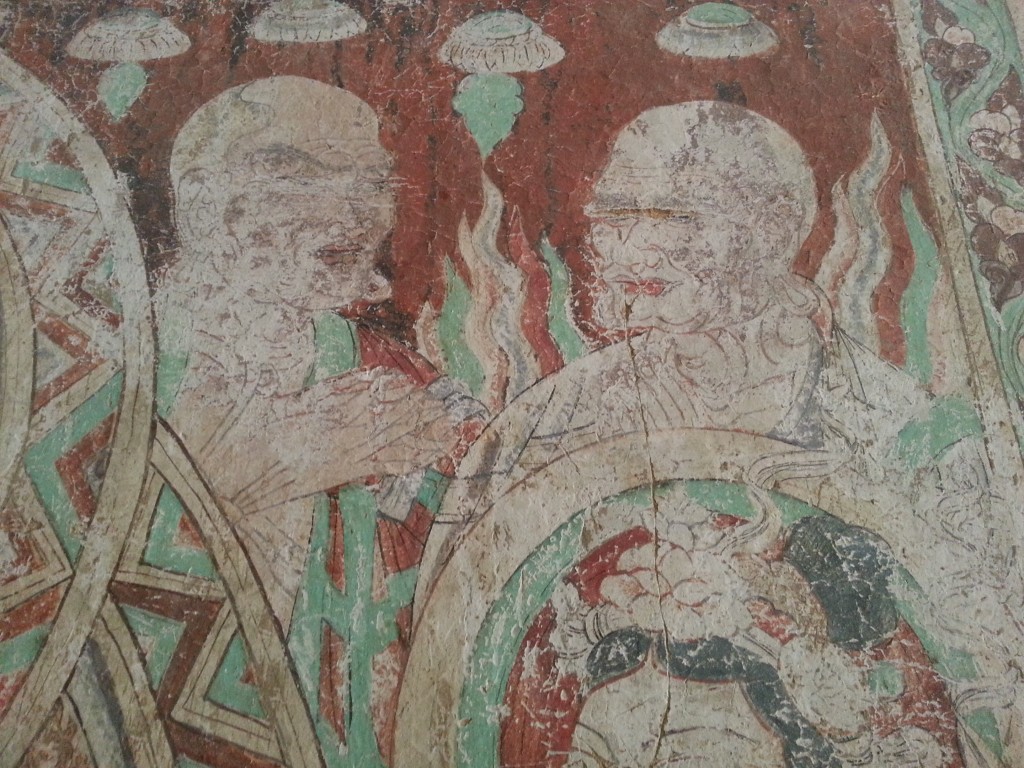

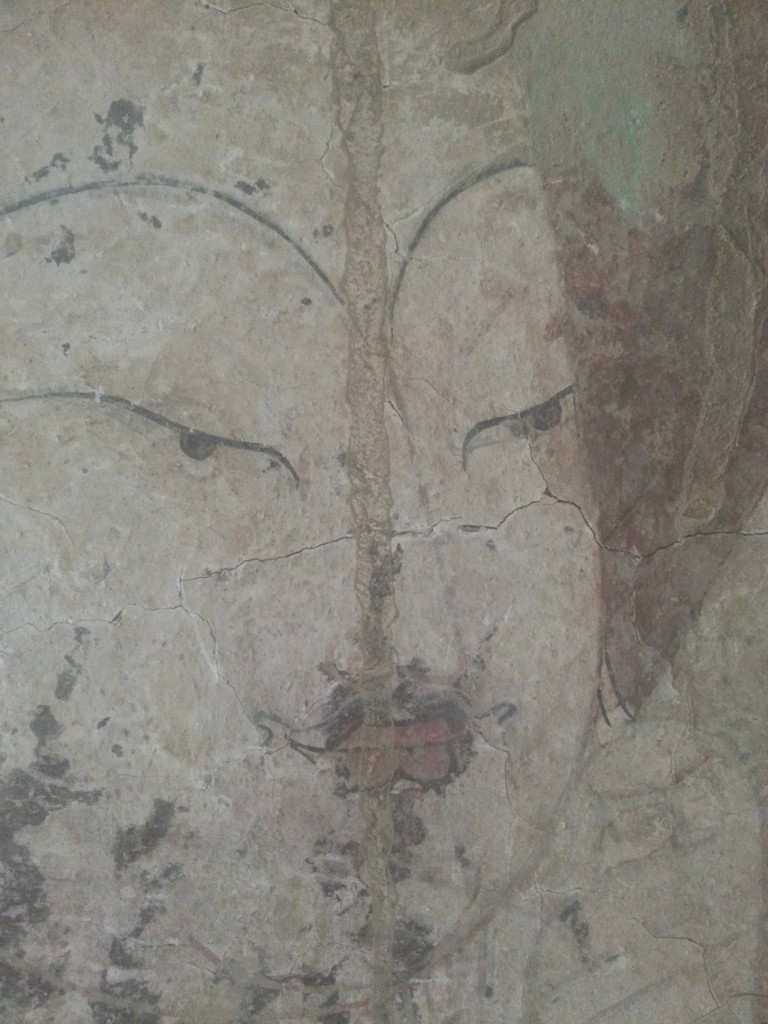

Still, the artwork that is still left in these caves is fantastic. From what I have been able to find, most of the paintings are from the ninth to thirteenth century. This was the period when the area was ruled over by Uighurs from the nearby Silk Road Oasis of Gaochang in the Kara-Khoja empire. During this period, Uighurs were largely Buddhist, though other religions competed with Buddhism, though Manicheism and Nestorian Christianity also made strong showings among the Uighurs and the rest of the people living in Gaochang.

It was in this context that these caves were painted with beautiful Buddhist artworks. The financing was provided by rich nobles and merchants, grown fat off Silk Road trade, and, like the Indulgences that Martin Luther railed against, this functioned as a sort of spiritual accounting system. If you financed Buddhist artwork, it would buy you good karma and a better place in the next life.

And the artwork that remained was still vivid and a clear reminder of the trade in goods and ideas that once flowed past what is now a backwater. The people depicted in the artwork showed a variety of peoples passing through the area, though, more of the interesting ethnic paintings had been taken to museums far away.

One interesting thing is that, for some reason, no photos are allowed. We had seen signs, though the signs did not make it clear if it was photography or just flash photography that was not allowed. We assumed it was the latter, since the light from a flash can sometimes damage paintings like this, but we found out we were wrong when a security guard yelled at Galen when he had his camera out, shouting, “Noh, noh, noh,” the extent of his English vocabulary.

For the rest of our visit, that guard followed Galen around. However, the other security guards thought it was too hot to care, so I was allowed to wander unaccompanied.

While Galen distracted the one guard who cared, I took these photos surreptitiously with my phone.

As we were leaving, I asked the director of the Bezeklik caves, an middle-aged codger, why photos were not allowed. He told me, as I suspected, that the flashes of cameras can damage the walls. I asked why flashless photography was not allowed. The codger got ruffled, struggling for an answer. In the end, all he said were that absolutely no photos were allowed, and there was nothing to change that.