The next day, we went back to the Bezeklik. This time, we got rides from local vans leaving from Turpan’s bazaar, heading to the general area called Shengjin, an irrigated valley that drained into the canyon where the Bezeklik caves were. It was in this area that the mummies and the world’s oldest drug dealer were found.

The van was faster than we had anticipated, so we got to Bezeklik in the middle of the afternoon, the hottest part of the desert day. We had the van drop us off a few miles north of the caves. From where we were, we could still see bits of the Bezeklik compound, but the workers at Bezeklik would be hard pressed to see us.

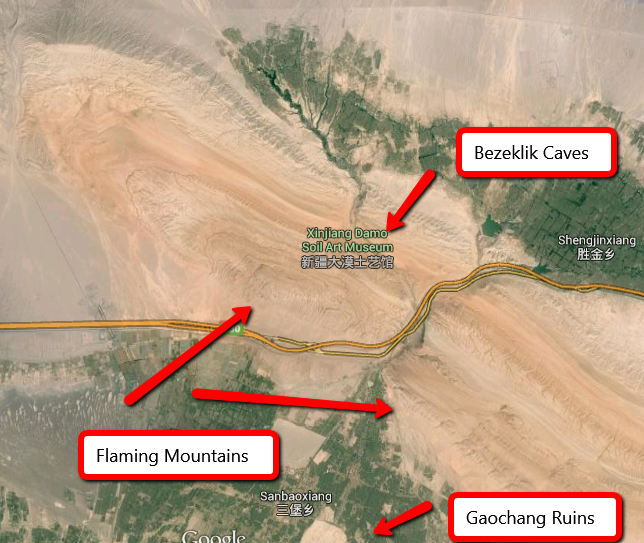

The bus left us on a flat plane of the road. To our right, the ripples slowly evolved into the precipitous drops of the Mutou Canyon, the river that ran past the caves. To our left, those same ripples moved upwards and became the Flaming Mountains, the red, whipped peaks that erupted from the Taklimakan Desert.

The sun beating down on us, we had no choice but to retreat into shade. We found a road down into the canyon. After searching for a few minutes, we found a perfect camping spot: flowing out of Shengjin, the Mutou River cut close to the canyon wall before cutting the other direction. At this point, a small desert glade, enveloped by man-sized bushes, opened up. We picked this as our campsite and escaped into the shadow of the cliffface, dipping our feet in the river’s cool muddy water.

For an hour or more, we waited, reading and napping. The sun made it dangerous to try to do anything until late in the afternoon.

Once late afternoon arrived and shadows stretched along the canyon walls, we hid our bags beneath one of the bushes and climbed out of the canyon. Bezeklik had already closed, but we were still careful to avoid being seen by anyone there. Two Americans camping will always be regarded as suspicious in China, particularly near caves where a bunch of Westerners had long ago stolen artwork Beijing considered its patrimony.

Up the sandy hills, we climbed out of the canyon, moving high up along the desert mountain. Our path was pock-marked with places that were once mud and had been dried to form ground that looked like smashed plates. Along the side of our path, the sun had baked the sand and the mud so thoroughly that it looked to have made bricks. Some of these emerged, half-hidden, from the sandy hillsides. It was hard to believe they were not hiding some ancient, undiscovered civilization.

From high up, we could see the canyon stretched out before us. To the east, all we could see were the side of the Flaming Mountains cut out by the Mutou River. Unlike the fiery red we had seen before, this face of the mountains glowed yellow, like some golden shivs erupting out of the earth.

To the north was the green valley of Shengjin, surrounded on three sides gray-brown desert. Beyond that lifeless expanse the Tianshan Mountains arose, making our Flaming Mountains appear as mere hills.

Above us a small, dirt road had been cut into the mountain, but otherwise, there was no sign of a human presences. The sand swallowed any human footprints. I had trouble imagining anyone had walked through here for years. The landscape was desolate. The road, long abandoned, made the place seem more, not less, forsaken.

Long ago, this place had once been a center of culture, a place of learning. How many people had passed here when this place was important, I wondered. How many Buddhist monks had camped where we were camping?

But like Dunhuang, Bezeklik had become a memory of importance. Looking from our spot high on the mountain, I realized, these mountains had become wild once they had been forgotten. For much of our trip to Tianchi National Park, I had felt like I was in an amusement park. In China, it not the protected places that are best protected, but the places that are forgotten that are protected.

For those interested in camping at Bezeklik, check out this post I wrote for the Far West China blog. That post has a better section on how to repeat this trip.