They will not allow us to dance tomorrow. For five years, we have not been allowed to dance to celebrate Eid al-Fitr.”

– Uighur Tour Guide commenting on religious repression. Since riots in 2009 in Urumqi, the Chinese government has severely restricted religious expression. Though the government has not ended the sermon at the Id Kah Mosque, it has banned dancing, a traditional celebration at the end of the sermon. The guide was employed by the Chinese state, but he did not bother to hide his disdain for it.

It was supposed to be a happy day. The end of Ramadan, Eid al-Fitr, marks the end of Islam’s holiest month and, in many parts of the Muslim world, is a happy time, analogous to Christmas in the United States. However, it is not a happy time for the Uighurs. The Id Kah Mosque, its name meaning “place of celebration” in Persian, has increasingly become a place of control.

We awoke early on Eid. I grabbed one of Galen’s cameras, slipped into a pair of pants and rushed out the door to watch the crowds of worshipers develop around the Id Kah Mosque. As I was waiting for the elevator, I peered out the back window, looking out into a parking lot hidden behind our hotel. Instead of being full of trucks, as it normally was, regimented troops and military transport vehicles filled the lot. The hidden parking lot was being used as an operational staging point by the militarized police.

Startled, I pulled back. We were not supposed to be in that hotel. After spending a night in the hotel, we had found out that our stay there had been legally precarious. These troops had come here to stop riots, not to enforce hotel regulations. Still, if we were spotted, there would be trouble. The elevator whistled me down to the first floor, and I kept close to the inside wall, careful to keep out of the line of sight that the hotel’s backdoor might provide for any of the troops lining up.

Turning out of the hotel, I turned a corner into one of the old town’s main streets. Hundreds of Doppas, the square-ish hats worn by Muslim Uighurs, bobbed ahead of me as the sea of men drifted towards the Id Kah Mosque. On their way to the mosque, worshipers were forced to march past another cluster of police. The militarized police wore green uniforms; formed into phalanxes approximately five lines deep, the first line had shields and truncheons, the next lines of troops held high-powered rifles. To their side, a regiment of black-clad police stood, pistols strapped to their hips. Watching worshipers crowd past the security forces, I realized that these police were put there as a show of force. The guns were there to let people know that any rioting would be put down quickly and brutally.

I followed in the footsteps of thousands of Muslim men and boys, weaving my through the lanes of the Old City. Approaching the Id Kah Mosque, the sound of an abrasive language, Uighur or Arabic, rang out of speakers throughout the lanes. The call to worship had already begun.

The sunrise at their backs, the men prepare themselves for worship, leaving a narrow passageway for other worshipers.

By the time I had arrived, around 6:30 local time, the alleyways on the side of the mosque were already filled with guys sitting with their feet folded beneath them on their laid-out prayer mats, their shoes neatly placed in front of them. Seven or eight rugs were laid out, taking up about four fifths of the alleyway, leaving only a narrow passageway for the men streaming into the plaza.

The plaza in front of the Id Kah Mosque, a wide area marked with concentric half-circles and pocked by planted trees, filled up slowly. The worshipers packing of the plaza occurred in stages, with many men milling around and talking in the back of the plaza. Then, at some signal I had not understood, those men would push towards the mosque and, in well-maintained lines, fold out their prayer rugs. The process repeated itself more than once until only a handful of feeble old men and smartly dressed Chinese tourists were left standing with me along the edge of the plaza.

I should point out, my use of words like “men” and “boys” is intentional. There were no women gathered in the main group of men laying down their prayer rugs in the plaza. The only women I saw praying were a group of four frumpy looking women, probably middle-aged, who were fully covered, with only eye slits showing their face. They had sequestered themselves off to the side of the plaza, in an alcove at a nearby shop, praying like the men, just in their own separate quorum.

Other women came, but did not participate in worship. I saw one grandmother who had brought her granddaughter to watch, cutely dressed in a flamingly bright pink outfit. Another group, a gaggle of four teenage girls edged into the plaza and sat beside me. No one seemed bothered by their presence, though the girls were both tense and giggly, as if acting upon a dare.

Mostly, though, I watched the men in the plaza worshiping as the sermon continued. At certain points, it became more rite than sermon. On the call of a single voice, ten thousand men would suddenly twist their heads to their left, and then at another signal to their right, then stand, then sit.

This was followed with surprising uniformity, though, along the edges, there were a few men who could not follow the imam’s instructions. A deaf man along the edge of the plaza, separate from the mass of men, was still standing after everyone else had sat down on their prayer rug. A woman in an orange and brown hijab, probably his wife, came behind and gently pushed him down. Later, four brothers in red polos with white polka dots had to guide their toddler brother in the prayer service, as he seemed to get too distracted to pay attention to the instructions.

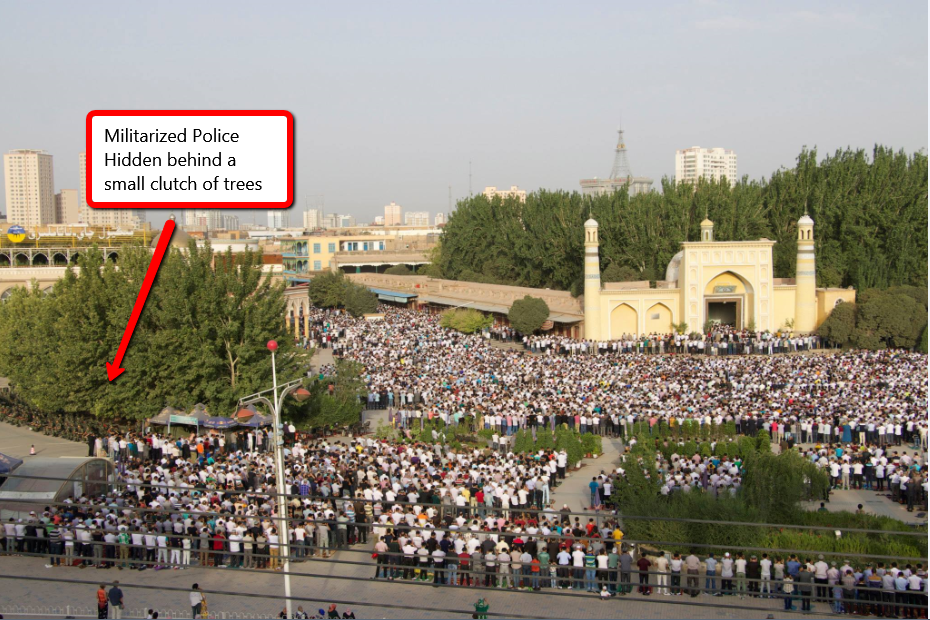

Despite all these stories of people worshipping their god as they saw fit, another power loomed uncomfortably in the background: the Communist state. Like at the entrance to the Old City near our hotel, a division of militarized police stood in the square, hidden behind a row of trees that appeared to have been planted just so that these police would be obscured from the view of tourists’ cameras, though the worshipers were all aware of their presence.

This division of militarized police had about one hundred men, wielding riot shields and guns. Behind them were parked ten vehicles, several urban tank-like vehicles, troop transport vehicles, two fire trucks, an ambulance and a jeep (for the commanding officer). The urban tanks had machine-guns mounted on top to shoot through any rioters and plow to make it easier to run over demonstrators without having them getting caught in the tires. Plain clothes Uighur police officers had been stationed along some of the entrances, and cameras were watching each move in the heavily choreographed ritual.

The sermon ended, and the crowds quietly dispersed, some taking selfies in front of the mosque, others getting pilaf before heading home. They seemed glum, but the orders were clear: no dancing.

I do not blame the Chinese government for having riot police at the ready. The threat of violence was real, as we knew from the riots that had broken out in Yarkant and the violence that, though we did not know it then, would come the following day. I do however worry that this show of force is the only solution that the Chinese state has really come up with, and that is the heart of the problem. Instead of pulling out the problem at its roots, what they are doing is more akin to mowing the grass, cutting it down temporarily, only to see it rise back up soon.

These photos are a mix. Some are from Galen, some from Lee. All photos taken from high up are Joshs photos, the Xinjiang entrepreneur who writes at Far West China.