Volleyball at the Edge of the World

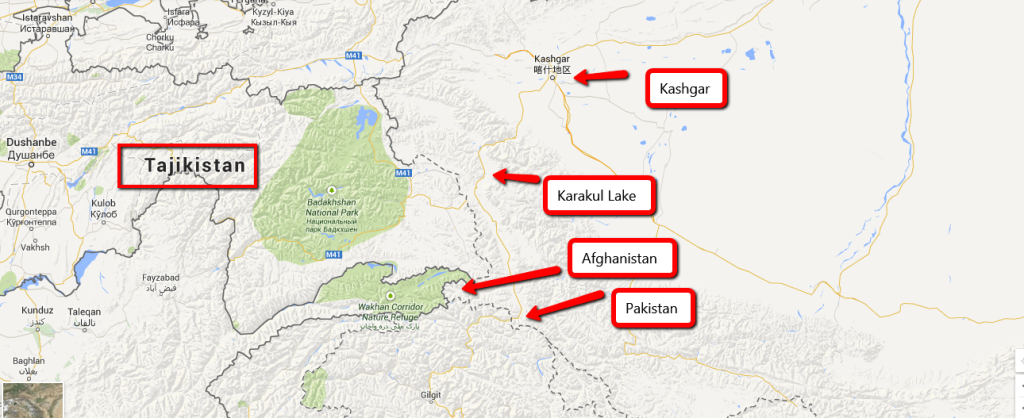

We were far off the beaten path now. Where we were, Karakul Lake, we were as close to Beirut as we were to Beijing. We were fifteen miles from Tajikistan, fifty from Afghanistan. Our driver dropped us off at the lakeside and told us that he would probably be coming back in the afternoon the next day, and that we should call him if we wanted a ride.

Karakul Lake is a small blue diamond perched in some of the highlands of the Pamir Mountains. The lake sits at about 12,000 feet above sea level. Beside it towers the massive 25,000 foot monster peak, Muztagh Ata, the forty-third tallest mountain in the world. In the distance, we could see a small tourist enclave with gift shops and tour bus parking, where you were charged for a ticket to see the lake that, if you just walked to where we were, you could see for free.

We avoided the touristy area and paid for a night and a meal in a lake-side yurt owned by some Kyrgyz shepherds. Once we dropped our bags in the yurt, we found a series of intertwined paths which herders used to circumnavigate the lake. Two boys in off-brand wind suits and tennis shoes, their batman hats turned to the side, bumped past us on a motorcycle, screeching “herrrro” as they passed. Several times, we were passed by shepherds, using their motorcycles to herd yaks, pulling up on either side of the yak to nudge them if they were going the wrong direction.

Herding had, until recently, been the only way to survive here. The high elevation would not support farming. Herd animals were scattered across the landscape: yaks, goats, dogs and sheep. The dogs had surprised me; Muslims generally do not like dogs, finding them to be unclean. When I asked some of the Kyrgyz about the dogs and Islam, they shrugged. They liked dogs and did not care about Islam’s hesitancy towards canines. Kyrgyz were laid back Muslims, drinking beer and owning dogs.

Hiking farther, we ran into some of the young shepherds who had passed us earlier. They had taken a break from herding to play volleyball. Their flocks of goats and sheep dappled the nearby hillside, gnawing on grass, the kids and lambs scuffling with each other on the rocks above the court. The volleyball court was nothing more than a rectangular plot of dirt bifurcated by a limp net. A motorcycle was parked at the court’s edge. Behind them arose a dozen gray yurts and dirt-brown hills. Looming over them all was Muztagh Ata, his white peak lost in the clouds. We joined the shepherds for half a game, playing a few points before they dispersed, needing to tend to their flocks.

Evening came quick and cold. The Kyrgyz who owned our yurt provided us with pilaf and tea, and we relaxed with some French and Dutch mountain climbers who had, earlier that day, returned from climbing Mutzagh Ata. The French climbers were hard-core. They were the type of mountain climbers that considered Mount Everest beneath them, too crowded, too touristy. One of them had summited three of the world’s fourteen peaks above 8,000 meters (26,000 feet). They told us that Mutzagh Ata, despite its height, was a fairly easy peak to summit. It required climbers to be fit, but they did not really need any technical training, since the mountain rises like a nice, sloping plane. This plane is so smooth that, after summiting, most people ski back down the Mutzgah Ata, making the world’s longest, greatest ski trail.

We finished off dinner, and night came. Though the day had been warmish, the night was cold. We returned to our yurts and wrapped ourselves deep in the blankets provided.

Galen,

Good piece of reporting! Bravo!

zvezuk