I was satisfied with biking out to the Ruins of Jiaohe and the Emin Minaret, but we really wanted to get back to hitchhiking.

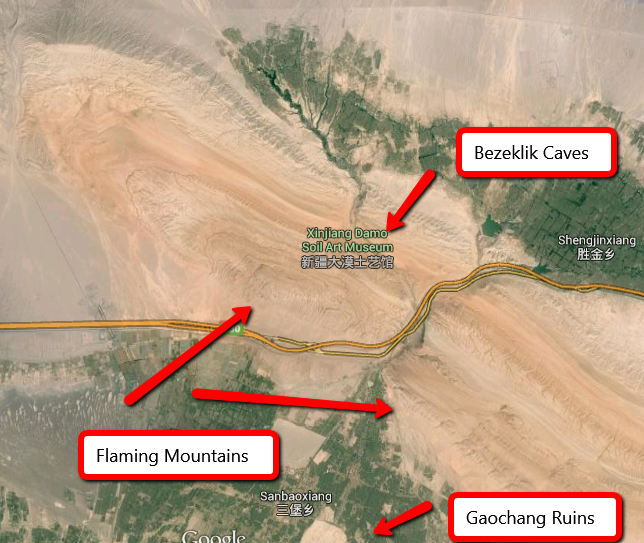

We took a bus out to the rural town near the Bezeklik Caves, Erbaoxiang, or Second Fortress Village. After a forty minute, twenty plus mile ride across the desert, past the south face of the Flaming Mountains, we were dropped off at an intersection in a rural village and pointed in the direction of the caves.

Some villagers were doing repairs on motorbikes in a sort of dusty, streetside mechanic shop. I asked them if they knew anyone going towards the Bezeklik Caves, but all they wanted to do was arrange an overpriced cab for us. After arguing for a while, we left them, walking off in the direction of the caves, trying to flag down a ride.

Within a few minutes, a farmer on a small, three-wheeled cart pulled over. Someone was sitting on the lip of the cart’s bed. I spoke to the driver, but he could not speak Chinese. Galen and I exhausted the three words we knew in Uighur, and, through some wild gesticulations, were able to communicate to him that we wanted a ride in the direction that he was going, towards Bezeklik. He nodded, and we hopped into the bed.

We zoomed down this country road for a mile or two, the breeze shaving the edge off the heat. At another intersection, he stopped, pointing us towards Bezeklik. We hopped out of the bed, saying, “Rakhmat,” or thank you in Uighur, and he disappeared down a small dirt lane.

The desert sun was approaching noon, local time. We waited around for a few minutes, buying bottles of water and trying to flag down more vehicles. A handful of Uighur men were gathered in the shade, looking down at something. I squinted to see what they were all hunched over.

I was startled. It was something I had never seen in China: a chess board. The Chinese have their own version of chess, but they have a completely different board; pieces occupy the intersections of lines rather than checkered squares and the board is bifurcated by a river. Immediately, I realized that the Uighur men were not playing Chinese chess, they were using the chessboard familiar to me. Soon, we were able to flag down a Uighur kid in a new sedan.

“We’re going towards the Bezeklik Caves. Are you going that direction?” I asked him. “Sure. How much are you willing to pay?” He replied. “Oh, we’re hitchhiking. We are looking for rides that don’t cost money.” He thought for a moment. “Okay,” he said, waving us in.

Over the fifteen minute ride, weaving through a canyon that cut through the Flaming Mountains, our conversation wound through the channels familiar to any foreigner who has had a conversation in China, where we were from, where we were going, how long did our flight take. The kid was young, probably not yet twenty. He wore the white cap that more devout Muslims wear. The sedan clearly was not his, but a parent’s or older family member’s. He drove carefully, as though he was not used to it. As we chatted, it was clear that he was interested in us. I wondered if he had seen us looking for rides and taken his family’s new car just so that he could meet us.

We came upon the parking lot of a tourist attraction. It looked a little kitschy to be ancient Buddhist cave artwork, but we got out anyways, saying “Rakhmat” and waving goodbye. The kid turned back around, going back the way he had come. We went to the ticket stand, but, it turned out, we had been dropped off at the wrong place. This was another tacky tourist attraction, something having to do with the Journey to the West and Uighurs, a vague amalgamation of a lot of the stereotypes that people from the Interior China thought about Xinjiang. The caves, the ticket man told us, were a half a mile further down the road.

The sun baking down on us, we ambled on. Two things occupied my thoughts as we walked. First, it seemed clear that the kid who had given us the ride had just been doing it to meet us. He had not been going this direction. He just wanted to talk to us. Second and stranger was that, though he grew up only a few miles from the Bezeklik Caves, he was not familiar enough with them to know where they actually were. He had probably never visited the Caves himself. Why was there such a disconnect? He was Muslim and the caves were Buddhist, but it was possible that some of his ancestors had lived in the area when the caves were painted, that other ancestors had come from faraway lands, traveling in the same caravans that carried Buddhist missionaries and artisans. Why was his connection to this art a stone’s throw from his home so tenuous?

Ah, man, I’m gonna be so sad to see these posts come to an end! I’ve found them riveting. As you may remember, I’ve visited the ends of the Silk Road, Xi’an and Tashkent, but not the heart…and prob’ly never will. You guys have filled in the blanks in a very significant way, and I’m grateful to you both.

Tom