The Tomb of Yussof Khass Hajip was in a quiet, leafy part of town, south of the city center. The entrance to the tomb was lined with grape vines, with shaded arbors on either side of the main passageway. At the entrance, there was a hulking block of carved chalk looming, for some reason, behind glass. It was a sculpture of Yussuf Khass Hajib.

Yussuf Khass was born in 1019 in what is today Kyrgyzstan, near Bishkek, but was, a thousand years ago, just a part of the Kara-Khanid Empire, a Turkic empire that spanned much of Central Asia. He was a famous scholar, so he moved to Kashgar, which was then the capital of the empire and one of the largest cities in all of Central Asia.

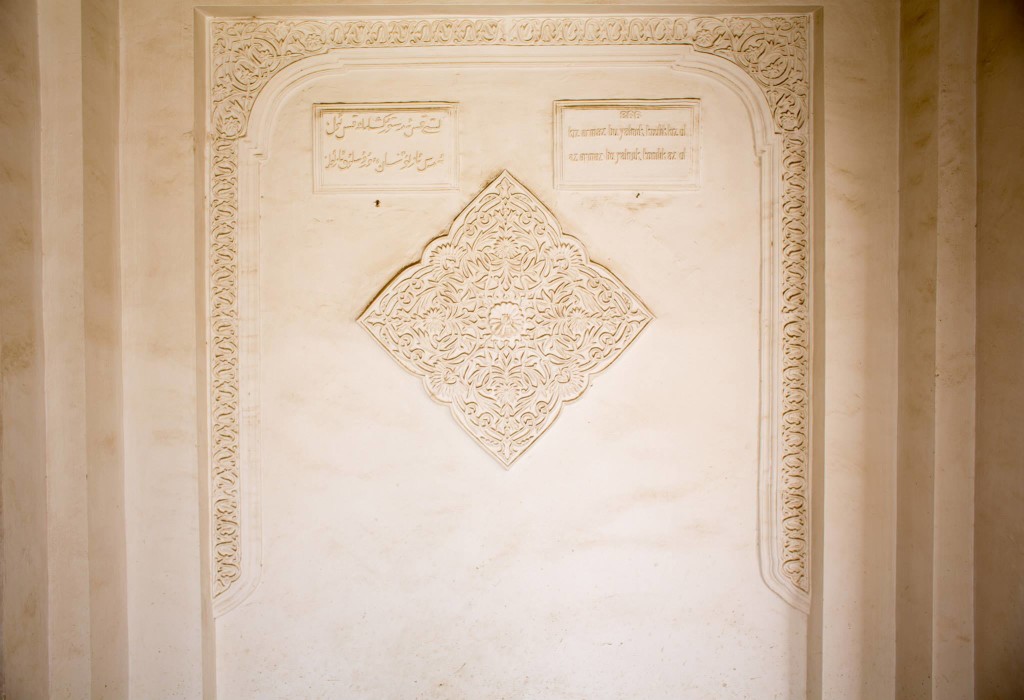

The tomb was small but majestic, with a Central Asian flair I had seen at the Taj Mahal, the blue and white shaded tiles forming geometric mosaics, arabesque walkways opening up to snapshots of windows. Bulging, minaret like towers decorated each of the corners, and the domed roof was speckled with windows.

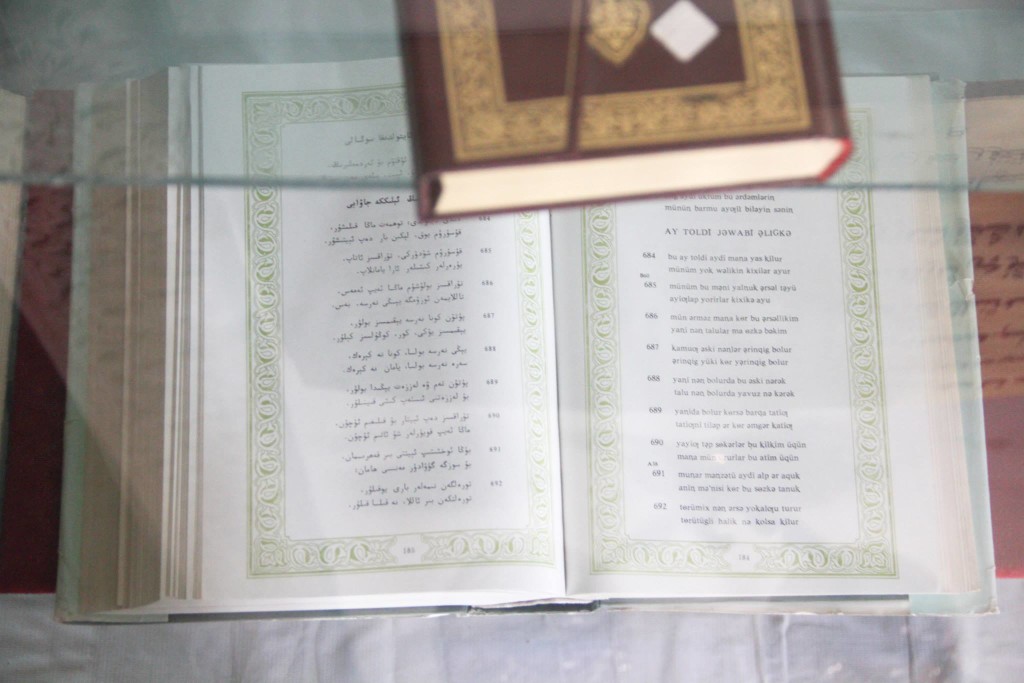

Yussuf Khass is most known for writing, The Wisdom of Happiness in Kashgar, completing it in 1069, then presenting it as a gift to the prince. The work is one of the greatest works in Turkic literatures, the group of literatures that spanned the Turkish speaking world before these places broke down into nation-states (Turkey) or were swallowed up by other empires (the Uighurs in the Chinese Empire, the Kyrgyz in the Russian Empire). The work is claimed as a major work by both Uighurs and Kyrgyz today, the Kyrgyz even reserving a spot for Yussuf Khass on their 1000 som note, equal to about $20 USD.

The Wisdom of Happiness is a poem, and it covers a large range of topics that tell us a lot about life at this time.

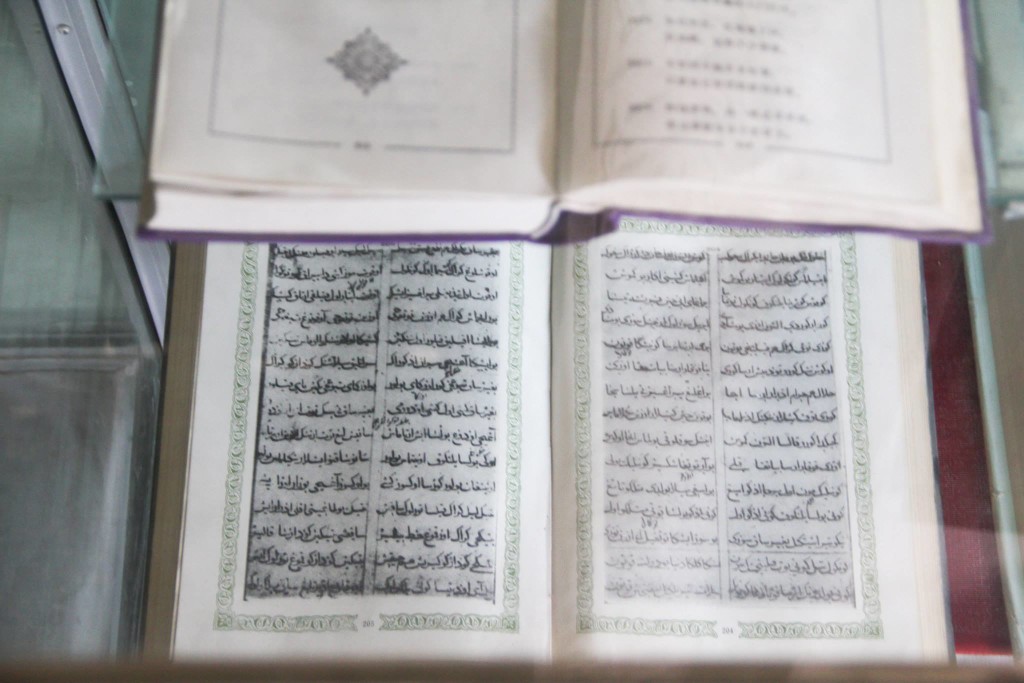

Inside the mausoleum, a sarcophagus sat atop a pedestal, draped in a thin blanket, its architecture mirroring the building’s blue-tiles and arabesque flair, a wick-like flame sprouting from the ground. Outside, there was a small glass case containing multiple imprints and translations of The Wisdom of Happiness.

The Wisdom of Happiness was almost lost to the world. Only three manuscripts survived, one making its way from Herat to Constantinople to Vienna, another being found in 1897, and another being found in Uzbekistan in 1943. Interestingly, no copies were found in China, and the work was not translated into Chinese until 1984.

Unlike his work, which was barely saved, his tomb disappeared. Originally built by the King of Yarkant, his tomb had been one hundred and thirty feet high. The building we were standing in, a shadow of its former glory, had been rebuilt twenty-five years ago, in 1989. The centuries-old tomb had been destroyed in the orgy of Communist violence during the Cultural Revolution. What we were seeing was only a pale recreation.

Galen: I have pix of similar tombs in Tashkent, Khiva, Samakand and Bukhara that use the same-colored tiles…many shades of blue…no reds! (too hot). Again, many thx! Tom

Excellent commentary.