Kashgar’s Urban Planning Museum was tough to get into, but it was worth it. Hidden behind the staid language of historians and economists and a skyscraper-speckled diorama was a story of the death of Kashgar.

China has a slew of these Urban Planning Museums. Normally, each museum has a section acknowledging that city’s inevitably glorious and unique past, the aspects of culture that this city has contributed to China. But then, there is a gigantic diorama of what the city will look like after all those unique things have been bulldozed and something stunningly modern will be built. No matter which city it is, each museum’s diorama looks the same: tall skyscrapers puncturing the skyline in two or three places, surrounded by phalanx after phalanx of modern apartment blocks. After the diorama, the exhibits that follow are exhibits explaining how the city’s government will achieve this vision.

Let’s take a closer look at the Kashgar Museum. An entire room is made to present the history of Kashgar but this is done to tell the viewer as little as possible about history. Take a look at these photos, of one of the larger exhibits in the Museum’s history section.

This exhibit took up an entire wall, but what did it tell us about Kashgar? Reading Chinese does not help much here. There is no explanation of why these changes occurred, no attempt at contextualization. Other than the line of text under each map announcing which year this new administrative division was enacted, we know nothing about these changes. Why are these changes important? We are not told.

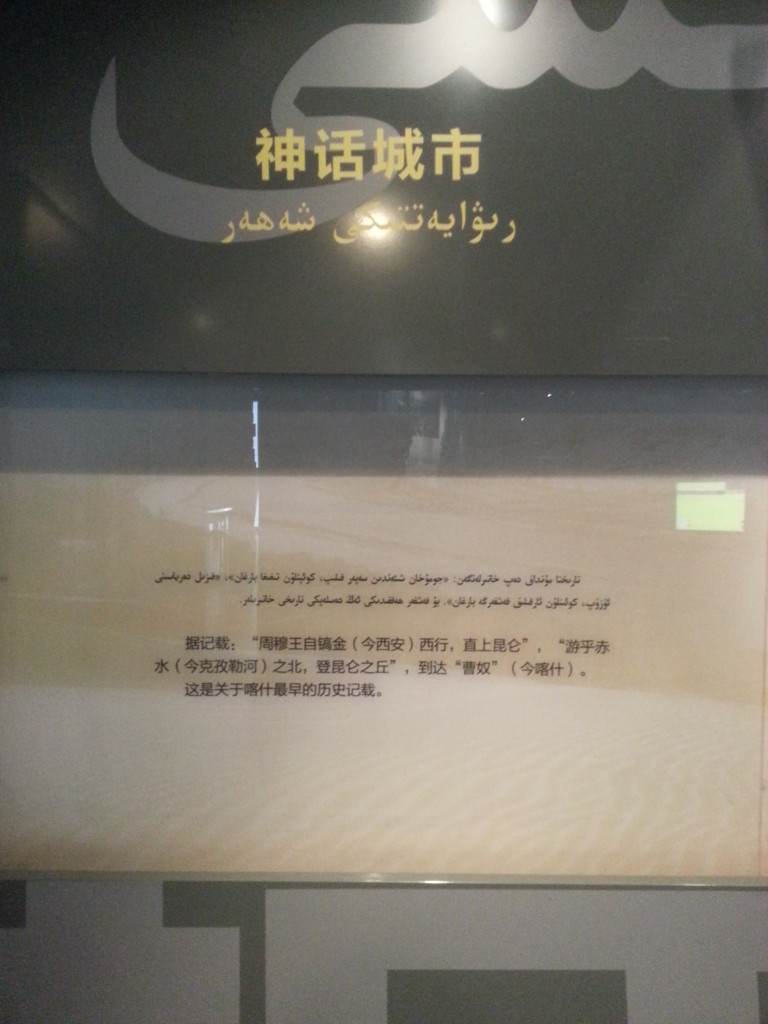

The Mandarin for the exhibit in the above picture is the title “Mythical City,” and it contains references from several ancient Chinese works to the Kunlun Mountains (to the south of Kashgar) and “Caonu” which they claim is today’s Kashgar. Interestingly, they only cite Chinese works referring to Kashgar. Nothing outside of China is important.

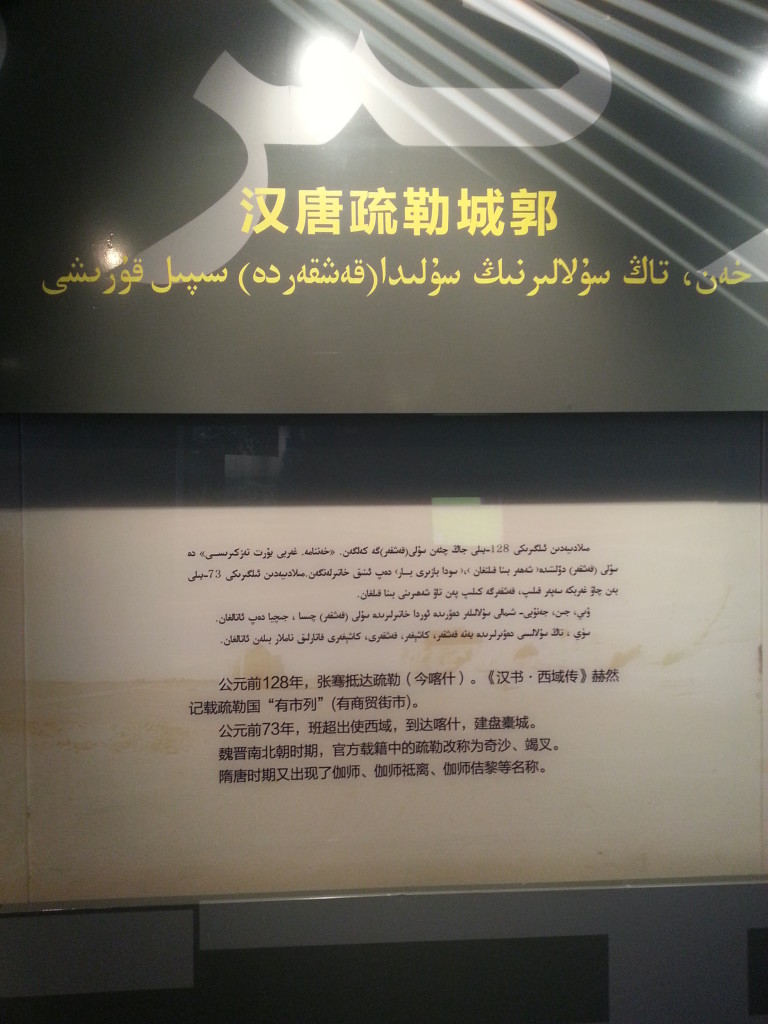

The above exhibit tells of how, in 128 B.C., a Han Chinese ambassador named Zhang Qian visited Kashgar. In 73 B.C., another ambassador, Ban Chao, also made it to the city. The exhibit goes on to note that for the next thousand years, Chinese officials recorded that the city had several name changes, each of which it lists.

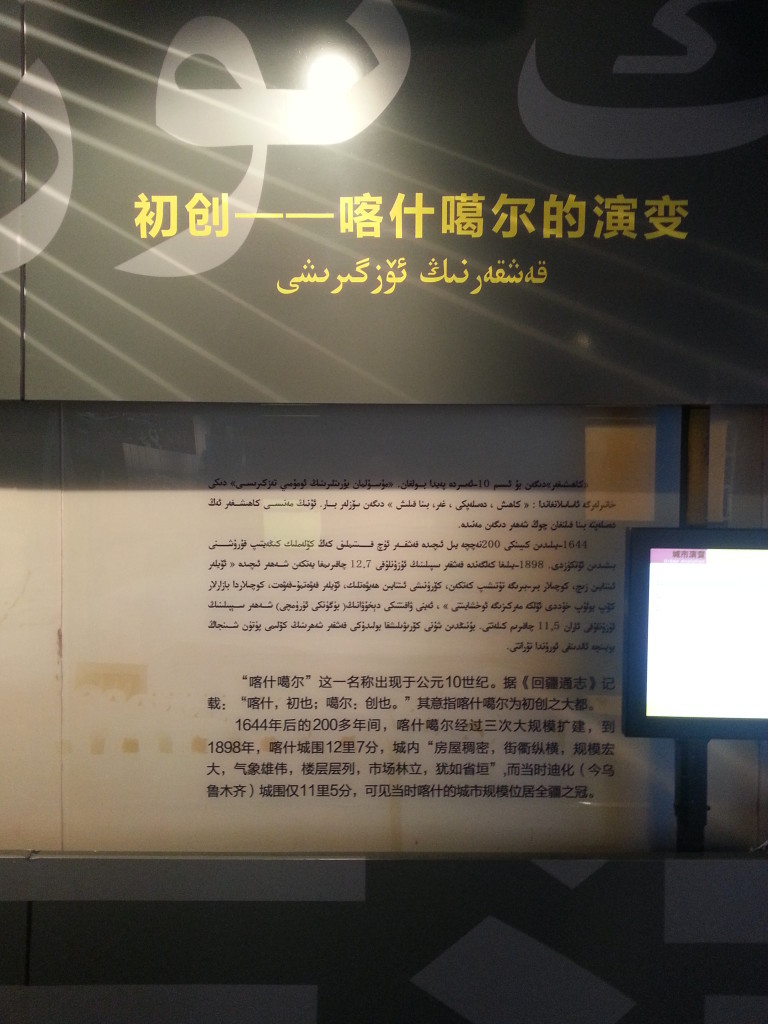

This exhibit mentions that the name “Kashgar” itself dates back to the 10th century. Then, the sign says that the city experienced three expansions since 1644. Finally, this exhibit spends the last half of the text describing the size of the city and its walls, using that to explain how this signified Kashgar was a major city in the border areas.

What I find fascinating is, in all these exhibits on Kashgar’s history, there is no mention of any Uighur name, any Uighur person, no mention of the arrival or importance of Islam in Kashgar. When history is mentioned, it is only in the context of Chinese history that it is done, and it is only done through Chinese sources.

From the history section, we moved into the diorama section of museum, the highlight of the museum. The following photo is shot with my phone looking down on the diorama from the second floor with the lights turned off.

And these four photos were shot by Galen with his DSLR, with the diorama lit up.

The vision the diorama presents is of a Kashgar that does not look Kashgari at all. There is nothing in it that is Kashgari. It could be anywhere in China, anywhere in the world. The diorama is thick with coniferous trees that do not belong in this desert city. The apartment complexes are just stock complexes that look more like Kansas City than Kashgar.

The diorama does suggest that, within this vision, the traditional Kashgari neighborhood on the hill which we looked at here and here will still be preserved, though, everything other than that neighborhood has been bulldozed. Also, the Id Kah Mosque appears to be preserved in some form, though all neighborhoods outside the area surrounding the mosque are razed, including Kashgar’s famous Sunday Market.

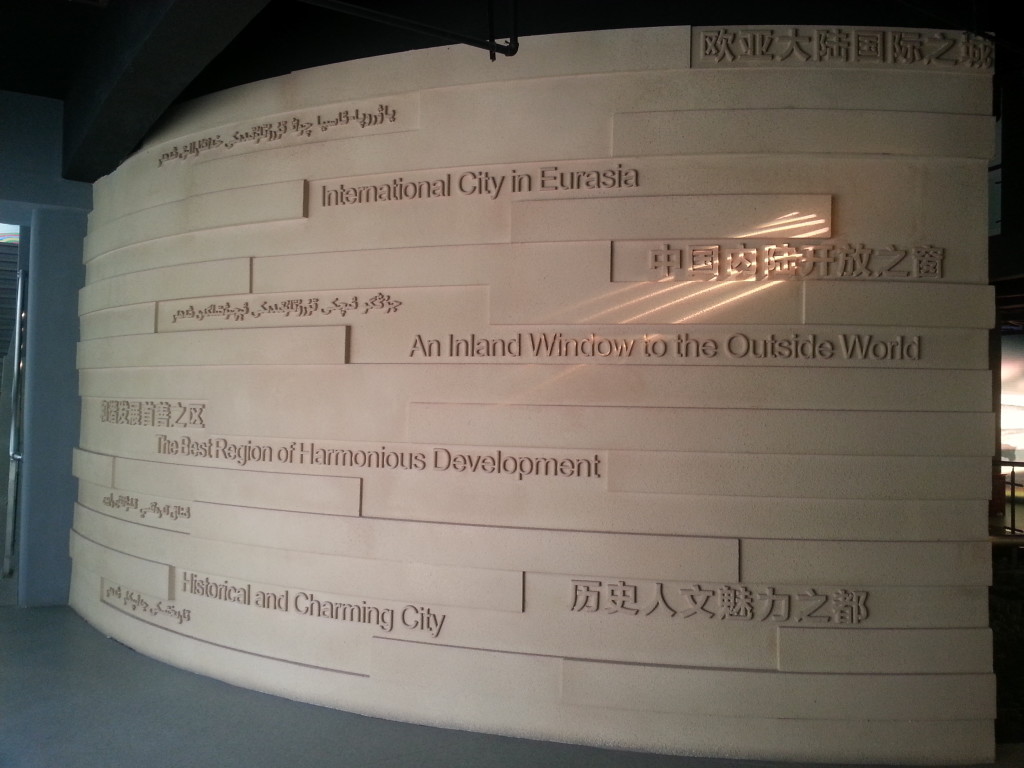

After the diorama, I wandered into the section dealing with Kashgar’s future. The wall that sits behind what would be the front desk (if the front doors were open) has several slogans carved into stone.

These slogans are everything that Beijing wants Kashgar to be, a Eurasian International City, China’s Open Inland Window, a Model District of Harmonious Development. This last phrase signals that the museum was built during Hu Jintao’s reign, since the word harmonious development was the slogan associated with his reign from 2002-2012, again, placing Kashgar in the context of what goes on in the reign of Beijing’s leaders, not local concerns.

Let’s take a closer look at how these exhibits describe Kashgar’s future.

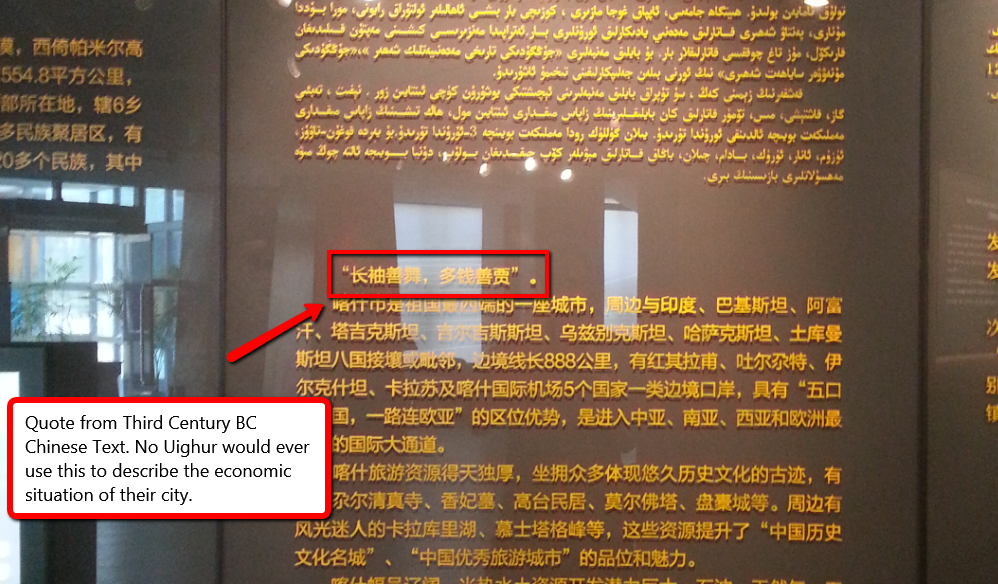

The exhibit pictured above, titled “Superior position and resources,” has three main paragraphs, each tackling a different topic. The first paragraph looks at Kashgar’s “superior position,” the city’s location on a border with eight neighboring or near neighboring countries. Its location is also advantageous because it runs along a line that leads from Asia to Europe. The second paragraph discusses the different tourist attractions that make it a prime target for becoming what is designated “China’s History Culture Famous City” and “China’s Superior Tourism City.” The final paragraph looks at different mineral and agricultural resources that Kashgar has the potential to produce. All of this is meant to imply that Kashgar’s prospects for economic development in international trade, tourism, mining and agriculture are all bright.

But the text in the photo begins with a short quote. The quote is taken from Han Feizi, a Chinese philosopher from the 3rd Century B.C., saying essentially, “With assistance, something is easily done.” This quote is meant to suggest that, with all the advantages that Kashgar has, in tourism, mineral wealth and trade, the city’s economic development will be easy. Yet, the quote also demonstrates that this exhibit and the others were written not by local Uighurs, who would have little knowledge of two thousand year old texts in a foreign language, but a Han Chinese, probably in a city far away from Kashgar. Again, this quote demonstrates that it is through the lens of Han Chinese history and Han Chinese sources that the museum’s designers wants us to view Kashgar.

The Museum is meant to be a vision of what Chinese authorities want Kashgar to look like in three decades. However, it reveals more than the government intended it to. Not once does this museum exhibit mention the name of a Uighur. All references to history are made through the lens of Chinese history, not Uighur history, not Central Asian history. And the future of Kashgar is exactly the same as it is elsewhere in China, a location without place, a city without its soul. In short, what the Chinese want is a Kashgar without Kashgaris.