Much of the land in these hills was desert, grey green scrubs punctuating the yellow dirt across vast stretches of plains, until they were swallowed up by the brown Tianshans or the blue sky. Small farms were carved out of the desert, green corn stalks and a lonely donkey standing against the desert. This was eastern Kyrgyzstan, the area surrounding Issyk-Kul Lake. Tiny towns flashed by us as we moved out of Bishkek and up into the hills, a mix of more Soviet-tinged European style houses and mud-brick hovels reminiscent of Kashgar. That was Kyrgyzstan really: a mélange of poor Central Asian and richer European elements.

Much of the land in these hills was desert, grey green scrubs punctuating the yellow dirt across vast stretches of plains, until they were swallowed up by the brown Tianshans or the blue sky. Small farms were carved out of the desert, green corn stalks and a lonely donkey standing against the desert. This was eastern Kyrgyzstan, the area surrounding Issyk-Kul Lake. Tiny towns flashed by us as we moved out of Bishkek and up into the hills, a mix of more Soviet-tinged European style houses and mud-brick hovels reminiscent of Kashgar. That was Kyrgyzstan really: a mélange of poor Central Asian and richer European elements.

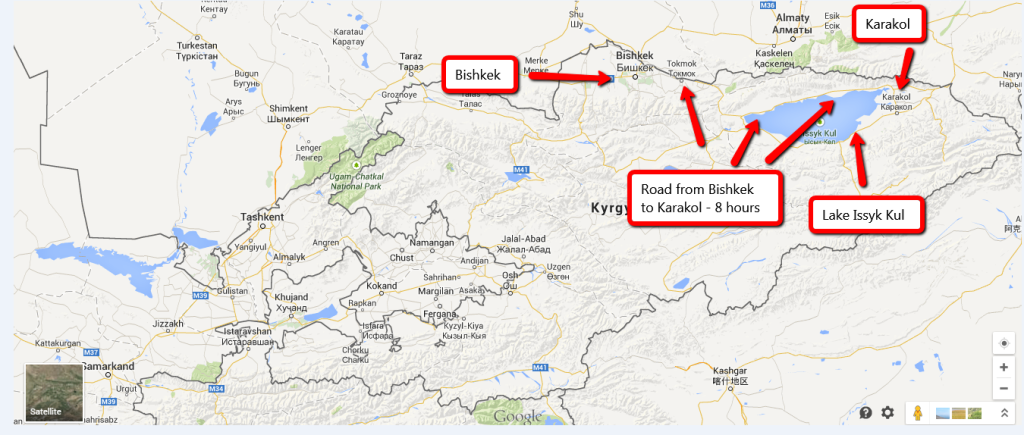

For our last hiking trip on the journey, we were heading to Kyrgyzstan’s most popular tourist draws, the giant Issyk-Kul Lake. Though half the size of the smallest of the Great Lakes by surface area, Issyk-Kul Lake is impressively deep, and weighs in as the tenth largest lake in the world as measured by volume. At some points, Issyk-Kul is more than two thousand feet deep.

The lake’s unusual depth and the fact that it is located in the center of the largest continent, far from the eyes of prying Western spies, made it an ideal testing ground for Soviet submarines during the Cold War. A large Soviet base had been constructed in Karakol, a town on the eastern end of the lake, and few foreigners outsiders were allowed in. For the first seven years that Galen and I were alive, it would have been impossible for the two of us, as foreigners, to get into this part of the Soviet Union.

However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Karakol’s cash cow dried up and the economy took a hit. Decrepit apartment blocks along unpaved city streets mark the points where the Soviet economy’s collapse cost everyday people their livelihoods. Though the Russians may still be using the eastern end of the lake as a submarine testing area, the people of Karakol and the area around Issyk-Kul Lake have had to struggle for other means to feed their families.

Now, this slice of Kyrgyzstan that previously forbade foreigners from entering has now become a tourist town. There is a logic for this move. Almaty, the economic capital of Kazakhstan and all of Central Asia, is only forty-four miles away as the crow flies (though there is no direct road there). However, the nearest ocean is fourteen hundred miles away, either by a ten hour flight or a forty-four hour drive. Issyk-Kul has become the beach vacation for those with no ocean.

We arrived after dark in Karakol, our destination on the lake’s east end. We had the van we rode in drop us off; the area was sketchy enough that we did not want to navigate our way through the unpaved streets of this unfamiliar town struggling in the post-Soviet economy. We checked into a yurt-camp hostel at the town’s center.

Dropping our bags onto our beds, we headed off to a restaurant that had been recommended to us, with other travelers claiming it had the world’s best shawarma. Downing pijiu and nibbling enormous pieces of barbequed lamb off of metal stakes, we ran into some people we had meet on the road in Kashgar. We got to talking and eating, and then a band started playing cheap dance music and things all went downhill from there. In this podunk town on the edge of the collapsed Soviet empire, dancing off several songs, we came to realize that it was not all that difficult to have a good time.