Note: If you haven’t already read the post about Huazangsi, click here.

We were moving up out of the city and on the mountain road by 5:45. Though the sun had not yet risen, light illuminated the brown, scrub-less hills. The air had not quite dropped to freezing where we were, but, in the mountains, it was well below freezing.

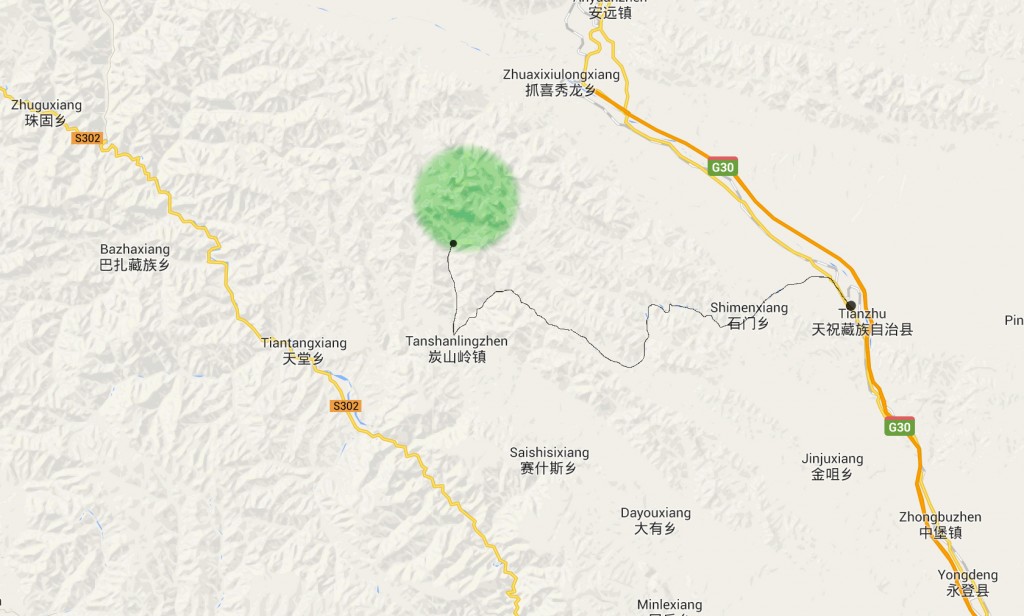

The trailhead up to the holy Tibetan mountain we would hike, Maya Snow Mountain, was more than two hours away from Huazangsi, the nearest town of any size. The road was dirt for hour long stretches, and our path was marked on one side by colored flags with the names of construction companies from places faraway in central China. They were constructing new sections of paved road or cutting into the alternating brown and green Tibetan hillsides.

Past the flags, the dirt road dropped off the mountain. Swinging around corners, our driver was occasionally confronted with the sight of coal-laden semis barreling down our side of the road. “They think it is safer to drive on the wrong side of the road…they are less likely to fall off the road,” our friend told us.

The areas surrounding the town of Huazangsi were mostly Han Chinese, tight-knit communities of farmers eeking a living off the bad soil in the mountain’s river bottoms. But as we moved into higher elevations, into the more rural parts of Tianzhu County, the Han and Tibetan population mixed, the two groups sharing villages. Even higher up, the soil was completely unarable and the people were almost all Tibetan herders.

Recently, large movements of Han Chinese into cities in Tibet has raised concerns that Tibetans will be completely sinocized, wiping out any trace of Tibetan culture. However, here it works both ways. Tibetans in Huazangsi speak little Tibetan, becoming sinocized but the Han Chinese who move into Tibetan areas and take up herding tend to become Tibetans. They take on aspects of Tibetan culture and dress, eventually becoming almost indistinguishable from Tibetans.

It was only 7:30, but the sky was a midday emerald blue. Our driver laughed as she scanned the horizon for clouds, saying something in the local dialect that I could only half understand. My friend laughed with her, turning to tell us, “She says that, a few days ago, some people went up to Maya Snow Mountain and the weather turned on them. It changes quickly if you are too loud. The lake fairies do not like it. When the weather changed on them, they got lost in the fog. One of them died up there.” Our friend turned back to the driver, adding, “But she doesn’t think that will happen to us.”

“I’m excited she thinks its unlikely we will die,” I quibbed.

Past a coal mine, we turned onto another road and the mood changed. The flags of the construction crews were gone. No more strip mining was to be seen. Lines of fur trees ran up along the ridges unmolested.

The local Tibetans felt it was warm enough to begin moving their flocks to summer pastures.We had been early enough to avoid any delays from the construction crews, but, because of the migration, we were caught several times in traffic jams with herds of animals moving to higher ground. Once, we were stuck in a herd of four hundred sheep, pushing our way through the herd for a full five minutes before we were able to return to a normal speed.

We pulled into the parking lot, a tiny square of dirt where the road ended. Craggy granite peaks towered over us. The mountain path rose before us, a series of stone steps snaking up the mountain. This was the beginning of the hike up Maya Snow Mountain.

This is the video of our approach up to Maya Snow Mountain:

Don’t miss a single video from our adventure. Click the red Youtube button below to subscribe!